Most teachers have a first-year-teaching story. Few have one like Matthew d’Alessio’s. His first teaching experience was at California’s notorious San Quentin State Prison, the largest prison in the country, where he taught math and geology in the Prison University Project, the only college program inside a California prison.

Most teachers have a first-year-teaching story. Few have one like Matthew d’Alessio’s. His first teaching experience was at California’s notorious San Quentin State Prison, the largest prison in the country, where he taught math and geology in the Prison University Project, the only college program inside a California prison.

“The students were among the most appreciative and motivated that I have ever met,” says Matt, who was one of an all-volunteer faculty of mostly graduate students from nearby universities. He’s breaching different boundaries now using Concord Consortium applications to teach science in an innovative way at the college level.

As a graduate student Matt worked at the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory. School groups frequently visited the lab and he volunteered to give tours. “I thought it was fun,” says Matt. “So I volunteered the next time and the next time.” Eventually he became the lab’s de facto tour guide.

When the lab received a request for a “science consultant” to help some middle school teachers develop curriculum, he stepped up for that job, too. “I had so much fun with the teachers that I was hooked on education for good.”

After he finished his Ph.D. and two postdoctoral fellowships, he taught high school Earth science at El Cerrito High School in the San Francisco Bay Area. His students traditionally struggled with science and were not necessarily bound for college, but they were curious about Earth science.

“Nature helped us get off to a great start. On my first day as a new teacher, in 2007, a moderate earthquake shook our community. My students came back the second day filled with questions,” he explains. So he created an activity in which students compared the seismic recordings from the earthquake to explain why some of them felt the earthquake at their homes while others did not.

Even though he’s now an associate professor of geological sciences at California State University, Northridge, he still uses that earthquake activity in his college classroom (often using recordings of the earthquake). Matt teaches introductory geology and physical science for future elementary teachers, science communication for geology majors, and an introduction to geoscience education research to graduate students.

He was introduced to CODAP (Common Online Data Analysis Platform) by a science specialist in a district he worked for. “He was raving about it,” says Matt. “He showed it to me and a group of teachers we work with and we were all instantly hooked.”

In class, he uses the basic graphing capabilities of CODAP to show how data can tell stories. One lesson looks at the relationship between rainfall and the Los Angeles River flow during a devastating 1938 flood. The city had to pave a channel to reduce future flooding. When students incorporate a variety of data spanning a century into CODAP, they discover evidence of human impacts on LA’s urban water cycle.

CODAP helps replace one of the barriers to data analysis (creating graphs) with a resource for asking and answering questions with data, he says. Students and teachers can easily explore the relationships between different variables by just dragging them onto the axes and noticing which ones correlate and which ones reveal interesting patterns.

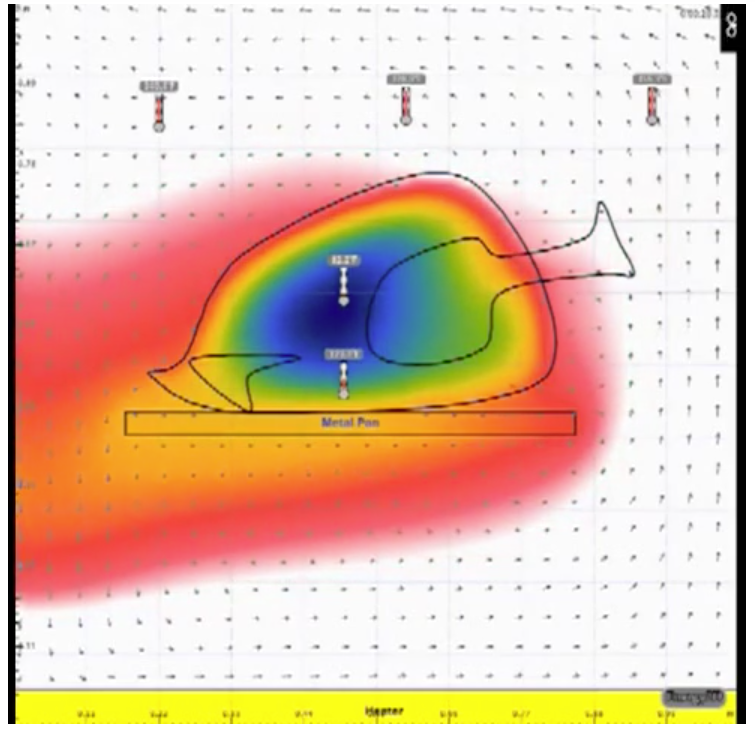

Matt uses other Concord Consortium tools as well. “My favorite tool is Energy2D,” he says. He uses it to simulate everything from mantle convection to building energy efficiency—all of which help meet the NGSS standards. He likes to use Energy2D for his physical science class. They make a simulation during Thanksgiving week of what happens when you cook a turkey!

Using Energy2D, Matt’s class simulates what happens when you cook a turkey.

When he pairs these simulations with Concord Consortium NGSS assessment items on heat flow, the combination helps students explore and explain thermal energy transfer at both the macroscopic and microscopic scales.

“It’s a big shift for teachers to give their students data and help them discover what’s going on,” he says. Instead of teaching out of textbooks in which all the answers are given, he likes using real-world data, and showing students how data can tell important stories.