By any measure, this has been one of the most stressful years on record, and teachers are among those most affected by the massive devastation wreaked by COVID-19. A recent New York Times article describes the emotional and physical toll of pandemic teaching, and we’ve heard directly from many teachers with whom we’ve collaborated for years that, faced with new responsibilities, they are truly maxed out.

So what’s working? What are teachers doing in these extraordinary times? Making connections—with science and with students.

Stephanie Harmon, who teaches physics and advanced physical science and Earth science at Rockcastle County High School in Mount Vernon, KY, and introductory astronomy at Eastern Kentucky University, is drawing on both new and trusted resources, like the Concord Consortium’s Earth science collection. She’s used two curriculum modules already this year, including “Hurricane Risk & Impact” and “What is the future of Earth’s climate?”

According to Harmon, the content has brought a sense of unity to her students: “Our area experienced several storm systems from hurricanes that made landfall in the Gulf of Mexico. While we couldn’t be together in the classroom, we were experiencing the same weather.” Using these modules has offered a “meaningful focus” to their work.

The web-based Earth science curriculum is designed for middle and high school students and includes embedded questions that are scaffolded to build understanding and simulations that allow students to manipulate variables and examine “what if’s.” They work in both synchronous and asynchronous environments. In 2019, Harmon co-authored an article for NSTA’s The Science Teacher based on her experience using the Earth science modules in her then-traditional face-to-face classroom to help students consider scientific evidence and develop scientific argumentation skills.

But teaching the same content remotely has pushed Harmon outside her comfort zone—and she’s okay with that, knowing that it’s a chance to model a willingness to try new things to her students because that’s what she regularly expects of them. Harmon notes, “The virtual classroom isn’t like the ‘regular’ classroom, nor should it be.” Her goal is to make the virtual space an engaging and innovative place for her students to talk and learn. “There is so much research on the significance of scientific discourse that it’s important to get the students talking. The discussions are rich and help the students process and develop deep understandings.”

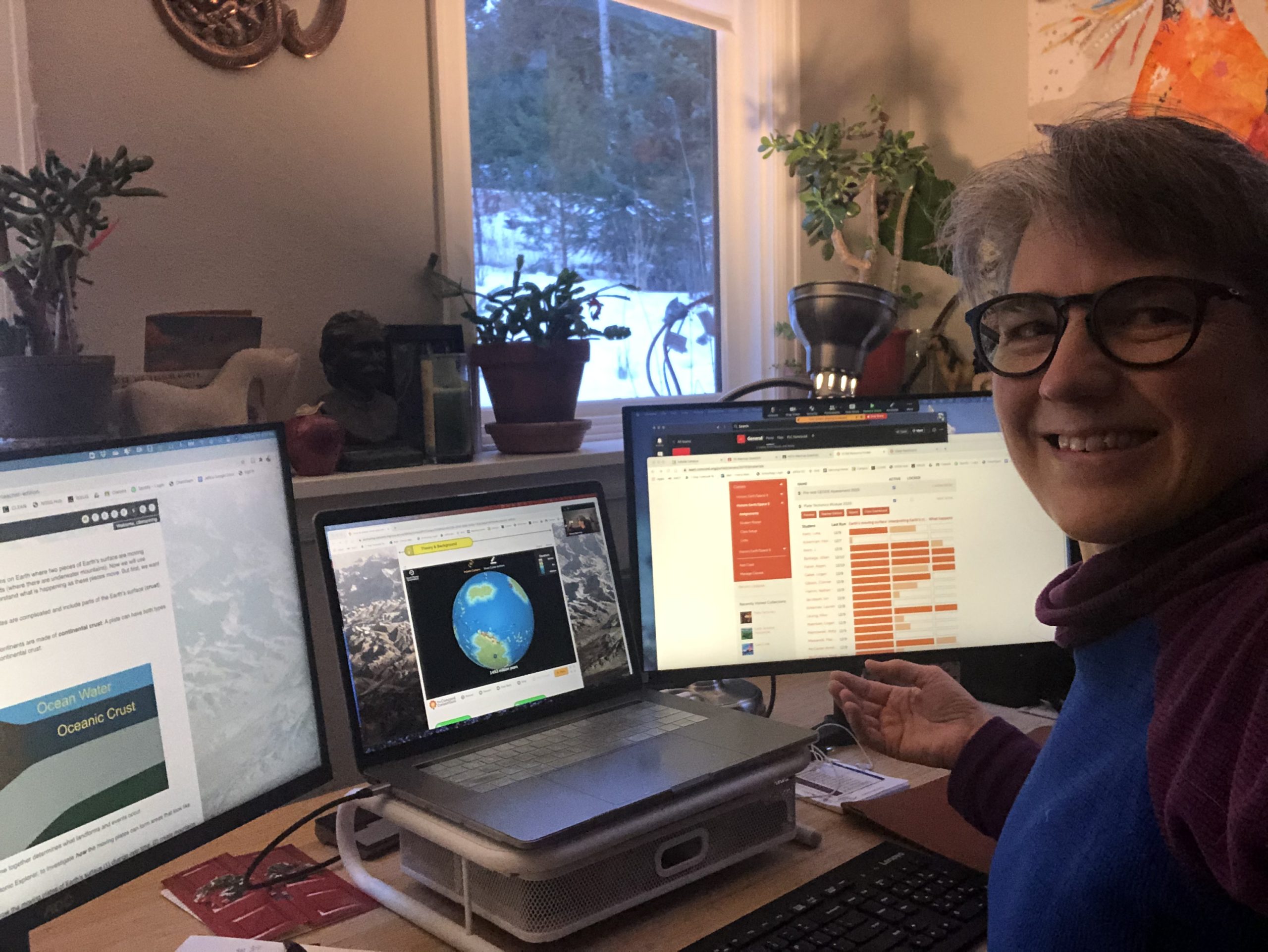

Using the online teacher dashboard available in each curriculum module, Harmon looks at trends in students’ written responses. When her class convenes in Google Meets, she uses Google Docs and Jamboard for students to make their thinking visible. More than understanding the particular Earth science phenomena, she views their study as part of the bigger picture of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) science and engineering practices, especially Developing and Using Models and Constructing Arguments from Evidence.

When they look at sample student responses together, Harmon guides students to develop criteria for what makes a good response (and she allows them to revisit their individual responses in the module and make edits at any time). This, she says, helps them understand how to clearly communicate scientific thinking and examine the merits and limitations of their arguments.

Rebecca Brewer teaches freshmen and AP high school biology classes at Troy High School in Troy, MI. She’s been using Concord Consortium resources for 15 years, including the deer mice evolution curriculum from ConnectedBio and the dragon genetics game Geniventure. Although she started this school year with hybrid teaching, she’s now fully remote and has found that the most adaptable tool for this environment is SageModeler, an open-ended system modeling tool developed for late elementary through high school aged students. Her students have used SageModeler to construct food webs, build biogeochemical cycles to model how matter moves, and generate evolutionary trees.

She notes that tools like Jamboard and Google Slides are great ways to keep students engaged in sensemaking and showcasing their understanding. These tools also “enable teachers to mimic practices normally happening in the classroom. From card sorts, to drag-and-drop style activities, to digitally building molecular models, to ‘grab-and-move-the-dot’ graphing—all these activities require active participation of learners.” She makes sure to follow up with questions like “What did we do? What did we figure out? What do we still wonder?” This promotes discussion, reflection, connections, and forward-thinking, she says, “the cornerstone of NGSS three-dimensional learning.”

Andrew Njaa is a physics teacher at Falmouth High School in Falmouth, ME. So far this school year, Njaa has been teaching in a hybrid model, able to meet in person with his students and use his remote time for short lessons and touching base with his students. Throughout his long teaching career—he’s been collaborating with the Concord Consortium for almost 25 years—his goal is for students to be able to apply scientific methods and research in the real world.

To help his students see the larger context of their studies, Njaa relies on tools, templates, and technology that is “seamless, intuitive, and powerful.” He’s currently adapting our high school InquirySpace curriculum materials and creating tables and other data starting points in our Common Online Data Analysis Platform (CODAP), then handing these documents to students for lab work. In Njaa’s experience, CODAP fits the bill as an intuitive way for students to work with and share experimental data. While NGSS practices all work together, constituting a broad definition of “inquiry,” the InquirySpace curriculum focuses on the NGSS practices of Planning and Carrying Out Investigations, Analyzing and Interpreting Data, and Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions.

Njaa advocates for trying things out before giving them to students and allowing extra time. But he’s also patient in his classroom, willing to “trust that learning is occurring even if it isn’t the learning you expect all the time.”

Cheryl Manning is an Earth science teacher at Evergreen High School in Evergreen, Colorado, which started with a hybrid learning model, but by mid-November had moved to fully remote instruction. She collaborates with fellow Earth science teachers at Evergreen: Ann Thomas, Nicole King, and Erika DuRoss. As a team, they’re devoted to NGSS three-dimensional teaching—integrating disciplinary core ideas with science practices and crosscutting concepts.

When a plate tectonics pre-test revealed student misconceptions, Manning was determined that students do more than read about the topic. With the Tectonic Explorer embedded in the “Plate Tectonics” curriculum module, students create their own simulation with up to five interacting plates on an Earth-like planet, draw continents, and apply force vectors to individual plates, then watch as oceans close, continents collide, mountain ranges form, and islands develop. According to Manning, some students were getting behind on the module “because they were having too much fun playing with the Tectonic Explorer!” Using the teacher dashboard, she’s able to see their progress in real time and to reach out to individual students to offer help or encouragement. And because students know she’s watching them, they are held accountable.

Manning’s colleague Ann Thomas used the new GeoCode “Seismic Hazards” module. Students construct computational visualizations using a block programming language to explain natural hazards and to make predictions about the probability of risks. Before jumping into the online curriculum, her students shared stories of earthquakes they had experienced. After Thomas introduced the activities during the class meeting, most students worked through them independently, though she went through the module step-by-step with her IEP students. She describes the value of trying things herself ahead of time and making screenshots of some assembled code blocks in the GeoCoder to share with students if they get stuck.

Colleagues Nicole King and Erika DuRoss also used the earthquake curriculum module, starting their students off with an Hour of Code tutorial from Code.org to introduce block programming. For King, it’s important to be available online during class time to keep her students motivated and to answer any questions in real time. She also logs into class early to chat with whoever else has logged on. King observes, “It has surprised me to find that those five minutes of personal connection time makes a much bigger difference than I expected. I look forward to those casual conversations with students each day, and I think it has helped us make connections to each other as a class.”

While Rebecca Brewer admits that remote teaching is challenging, she’s proud of her students who daily rise to the challenge of figuring things out. She’s motivated by them and determined to show them they are capable of hard work and are good at science. Stephanie Harmon agrees about the need for students to see the importance of science: “Never has there been a greater need for a scientifically literate society. This is a great teaching moment for science teachers. Our students need to understand that there is a scientific basis for what we are doing.” By committing to remote and hybrid teaching, Harmon and so many other teachers are working to stop the spread of a highly infectious and dangerous virus. This is pandemic teaching—stressful but critical.