In the past year, Karla Orosco has taught 7th grade science in person, remotely online, remotely and in person simultaneously, from home as well as from her classroom, to students locally and as far away as Italy. Needless to say, she has had logistical challenges, but mostly, she missed her students.

Orosco teaches at the Admiral Akers School, located on the Lemoore Naval Air Station in California, where they began remote teaching in March 2020. Students only started returning to the school part time—three hours in the morning—followed by afternoons online, in January 2021. The school decided that the continuity of coming to school every day was more beneficial than splitting the week into days on and days off. “We didn’t want parents to worry about what days kids are coming to school. We tried to make their schedule as uniform as possible.”

Orosco is a Master Teacher for Concord Consortium’s WATERS project (Watershed Advocacy using Technology and Environmental Research for Sustainability), a curriculum that builds water awareness among students, funded by the National Science Foundation in collaboration with Millersville University and Stroud Water Research Center. She had just finished teaching a final WATERS lesson when the quarantine hit in March. “I was the only teacher in the whole project who got to teach the unit in person as it was designed,” she says.

WATERS teaches about water quality issues using local data to explore geographic, social, political, and environmental issues related to watersheds. It includes an online portal of exercises plus UDL (Universal Design for Learning) support such as video and audio descriptions, and utilizes the popular Model My Watershed web app. For ten years every Akers student has been equipped with an iPad and every teacher a laptop, so they were comfortable using technology and navigating online.

Before COVID, WATERS also included hands-on labs in which students collected and analyzed local water samples.

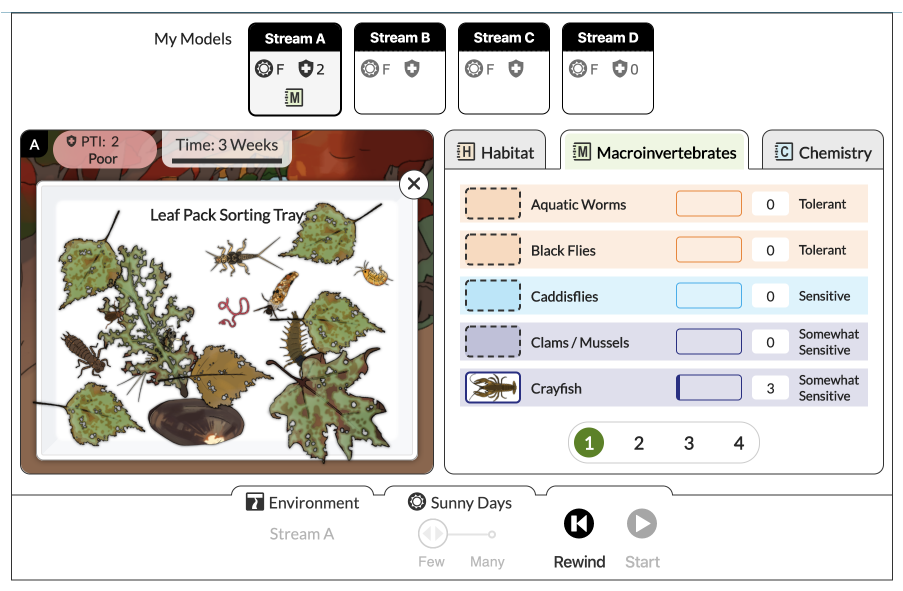

One way to collect macroinvertebrates is by placing packs of leaves underwater in a stream for three weeks. These leaves provide food and habitat for the macroinvertebrates, who move into the new neighborhood of leaf packs and enjoy the free snacks and homes! During COVID restrictions, students used a simulated version of the hands-on Leaf Pack exercise.

While much of the WATERS curriculum didn’t have to change to accommodate remote learning, our software developers created simulated labs to replace the hands-on field work. For example, instead of collecting their own local river water, students were given the results of a watershed environment similar to their own. In the “Leaf Pack” unit, they then identified and sorted the many critters in their simulated water sample using an online key.

The Leaf Pack simulation allows students to sort leaves and macroinvertebrates from their selected watershed environment online.

Even though the online lab simulations were not as exciting as collecting water samples and performing chemistry tests in person, “students did a great job on the first two labs and the third lab I almost like better online,” explains Orosco. “I thought everything in the simulations was well-designed and as good as it could be versus real-life experience.”

Macroinvertebrates can be many shapes and sizes.

Image: Stroud Water Research Center

Another challenge was the lack of in-class discussion and presentations. “It’s the challenge of COVID conditions,” Orosco explains. “You don’t get that rich discussion: What did you think about that? What did you recognize?” But students adapted well to Zoom’s chat feature when they were online together, and they replaced their in-person presentations with Flipgrid, a video discussion tool from Microsoft. However, once they were not “in class,” students didn’t work together much.

One of the things Orosco missed was talking to the students about her experience growing up in California, and how the environment has changed. “Water is like gold in California. Kids don’t know that. My students didn’t know where water comes from or where it goes. A lot of them are not native to here, so they don’t realize this is an irrigated desert. We used to have the largest lake on the West Coast, but it was diverted, and now the lake bed is farmland. Students are interested in those things.” The environmental changes she’s observed reinforces her belief in the importance of teaching about water resources.

The volume of adjustments—for teachers as well as students—in the past year is mind-boggling. Orosco is looking forward to getting back into the classroom with all her students. She has confidence they will survive the challenges of COVID and continue to experience the excitement of science. “These are Navy kids,” she says with pride. “They’re used to change.”