Alaska and Hawaiʻi have significant coastal regions that are important for their cultures and economies, but they are faced with threats caused by coastal erosion. Precipitating Change with Alaskan and Hawaiian Schools represents our commitment to bridging Indigenous and Western science approaches to understanding climate change and its effect on coastlines. Project leadership, staff, and teachers include Indigenous partners from both Alaskan and Hawaiian Native backgrounds. In July, the full team met for the first time in person in Hilo, Hawaiʻi, at the University of Hawaiʻi Hilo campus Ka Haka ʻUla O Keʻelikōlani College of Hawaiian Language to offer and participate in a collaborative professional learning event for teachers—and all of us. Even the building and grounds we spent our time in and on together hold layers of meaning for the project as a Native language learning space and recovery zone for native plants.

The Precipitating Change with Alaskan and Hawaiian Schools project is collaboratively developing classroom investigations for a coastal erosion unit with middle school teachers and students in Alaska and Hawaiʻi. There has always been coastal change and erosion, of course. It is the nature of coastlines to shift and change, with tides, with seasons, over decades and longer. However, both the island coastlines of Hawaiʻi near towns and the Alaskan coastline near ancient villages are eroding much more quickly and extremely than ever before. What do we know? What can we observe? What can we do? What is the best way to love our beaches?

One essential aspect of the curriculum is a glossary of natural science terms presented in English, Hawaiian, Yupʻik, and Alutiiq: the Native languages of the participating school communities. Every language communicates cultural understanding. For example, there is no word for “science” in Hawaiian. Natural phenomena have been closely observed by Hawaiians for generations and their understandings are communicated through moʻolelo or stories. Even data are kept and passed through generations using moʻolelo—from entire family trees tracing back hundreds of years to navigation routes between Polynesia and the Hawaiian Islands before the compass.

Both Indigenous science and Western science practices can inform our questions about coastlines. The curriculum weaves the two together, valuing both, to support young learners who live near beaches and coasts to build deeper knowledge and understanding of their local place. The unit closes with student-led class presentations to their communities based on their new learnings and enhanced place-based awareness.

Thus, our professional learning gathering in Hilo also wove Indigenous and Western science practices. To build our own collective knowledge and understanding, we shared several cultural experiences representing Indigenous science approaches.

We began by making lei out of “canoe plants” (plants the Polynesians brought to the Hawaiian islands in their canoes for building and sustenance). The ti leaf we used is significant for its protective qualities. Some intentions of our gathering are caring for and protecting our coastlines as well as each other as we build new bridges of understanding between our Western and Indigenous backgrounds.

Next, Hawaiian geologists demonstrated the Emery Method for profiling a nearby beach in Hilo, Hilo One (pronounced Oh-nay).

We waded into the water and climbed into Hawaiian outrigger canoes for a paddle into Hilo Bay to know the local water more intimately. We learned that Hilo Bay once sustained the most consistent waves for surfing in all of Hawaiʻi due to its geographic formation—like open arms facing north toward Alaska—until a seawall was constructed to allow boat traffic and provide safe harbor for commercial imports from around the world. When we visited, the waves were hardly lapping the shore.

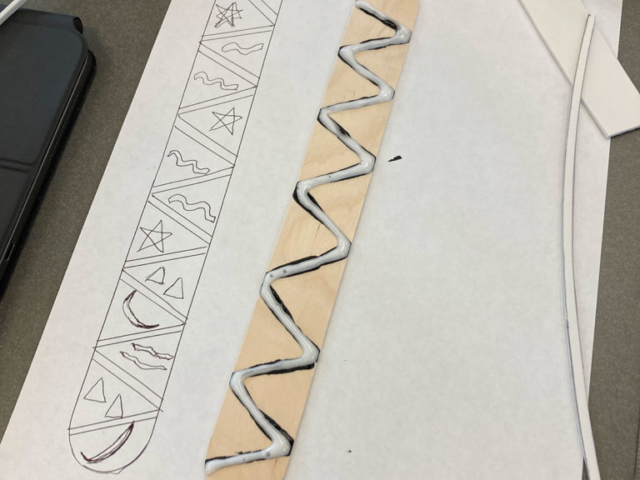

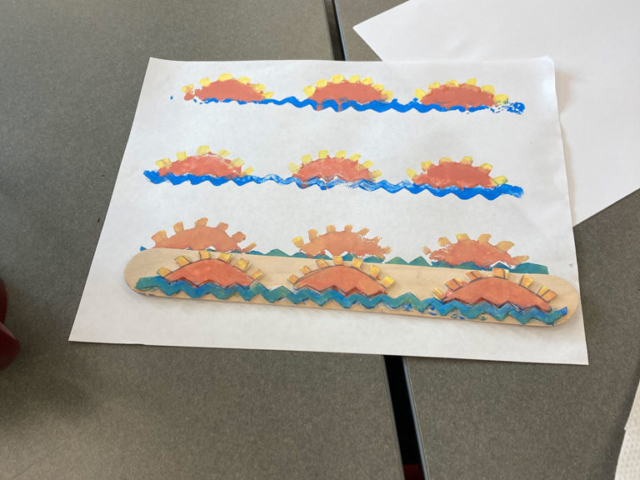

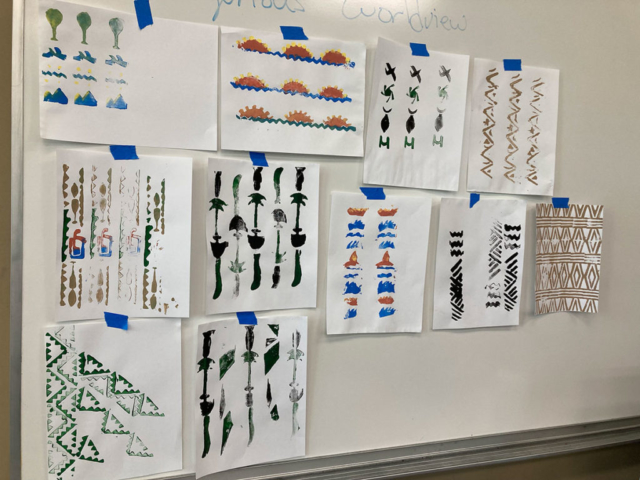

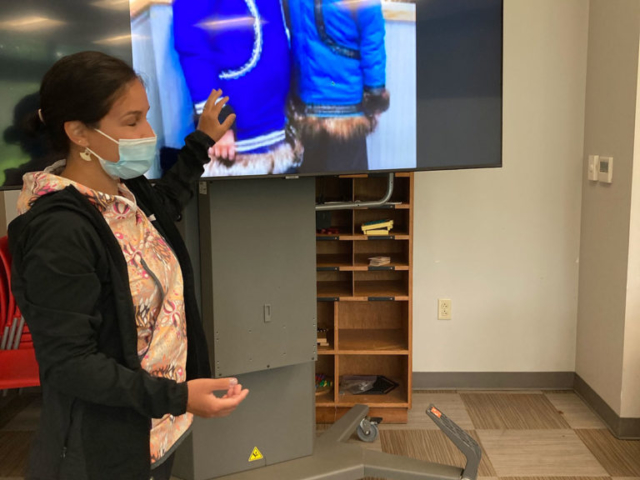

We also learned about and engaged in creating ʻohe kāpala (bamboo stamping), a Native Hawaiian art form traditionally used to adorn kapa (barkcloth) as a means of recording observations and stories – what Western eyes might think of as historical data collections. That art form connected easily with an Alaskan tradition of decorating clothing with family designs to share family heritage publicly. The Yupʻik translator showed us how to bead traditional style necklaces that represent family patterns in Alaskan tribal traditions. Even modern Alaskan natives wear their family patterns on their parkas, so that other more distant family members can recognize them.

But does bark stamping and beading relate to coastal erosion? From an Indigenous science perspective, definitely yes. Our place sustains our families. Knowing our places, like knowing our families, and their entire past history, is all connected to surviving, past and future. Knowing our place leads to love and dedication to our place, meaning listening always to what our place, our beaches, our coastlines, are telling us—through the stories of our Elders and our own stories. Western science can also tell us about a place, albeit in different ways, such as with tools for analyzing and displaying digital data.

Therefore, student participants of this project will also measure their beaches by conducting beach profiles and comparing their data with data provided by the University of Alaska, Anchorage geology labs.

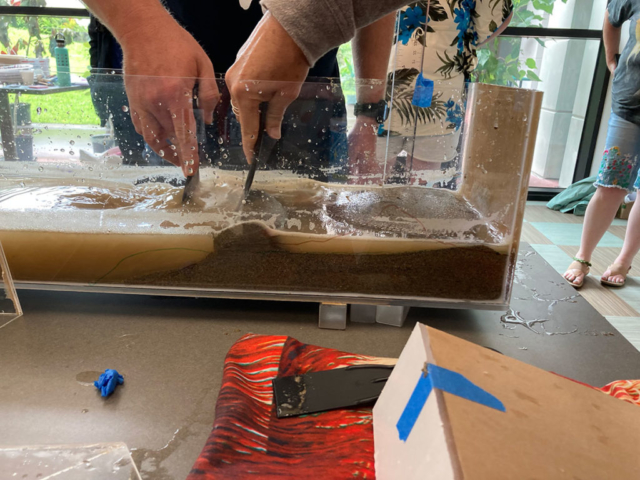

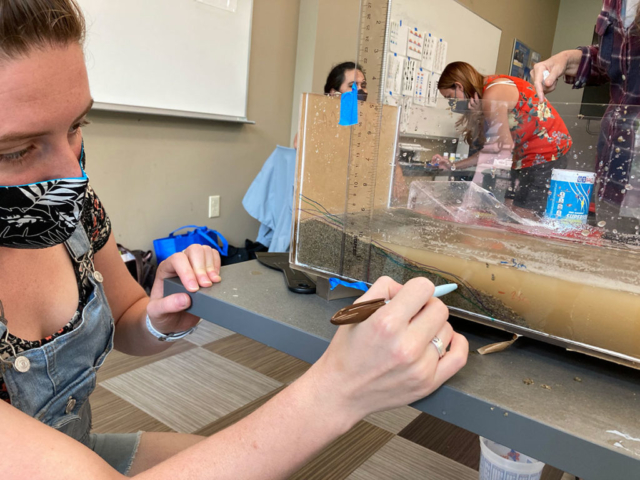

They will investigate wave action on beaches using wave tanks, with sand they shape with putty knives, measuring changes due to light and heavy waves created with a paddle. (Local students stopped by to explore wave action while teachers observed their activity.)

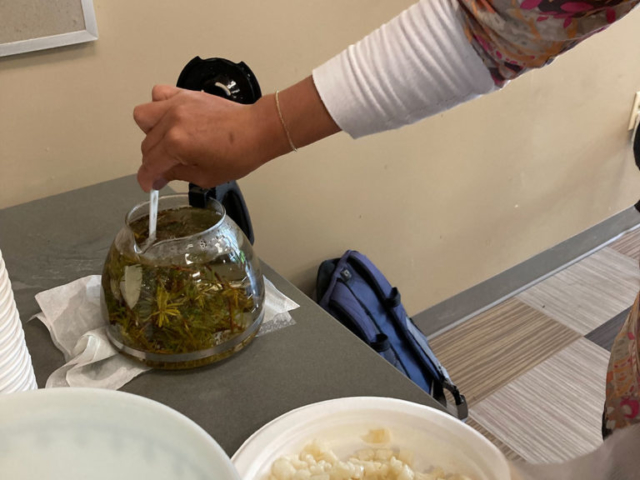

The Native Yupʻik language translator and a Native Alaskan Hooper Bay teacher made Akut’aq and Labrador tea for the group. With no Alaskan fish or salmonberries, the Native Hawaiian Principal Investigator shared a Hawaiian whitefish caught by a family member and we used that in one batch and raspberries, strawberries, white pineapple, and blueberries in another to make two kinds of Akut’aq (otherwise known as Eskimo ice cream). Sharing traditional foods bonded us with the communities we were getting to know.

The professional learning experience further committed us to co-developing a curriculum that values both Indigenous and Western science perspectives to investigate coastal erosion with youth in Alaskan and Hawaiian schools. Teachers in both states will pilot the curriculum in the fall.