Alaska is a place of superlatives. It is so big it encompassed four time zones until 1983, after which most of the state, except for the far western Aleutian Islands, was consolidated into what’s known today as the Alaska Time Zone. Its weather is colossal, too, blowing so fierce and frigid in the winter it can lock down many towns and restrict travel to “snow machines” (aka, snowmobiles).

Amidst this bigness are nestled many small villages, like McGrath, population around 350, on the Kuskokwim River in central Alaska, where temperatures reached ‑40°F in January. The combination of big state with small towns can be a challenge when it comes to education. Nathan Kimball, a curriculum developer for our NSF-funded Precipitating Change project, experienced some of those challenges working with students and teachers at McGrath’s only K-12 school when the thermometer dipped to ‑50°F and closed the school for a day. McGrath doesn’t cancel school for a mere snowstorm, but it does close when temperatures reach dangerous lows. “When it’s minus forty, people don’t go out much,” says Kimball.

Needless to say, weather and preparing for inclement weather is important everywhere, but in Alaska, the complications and hazards are uniquely extreme. The Precipitating Change project is testing instructional materials and technology for middle school students that help them understand weather and weather prediction by applying computational thinking practices in a fun and interactive format.

In partnership with Argonne National Laboratory, Millersville University, and University of Illinois at Chicago, the Concord Consortium has developed locally focused curricula for the Northeast U.S. and for Alaska. The Alaska materials will be tested this year in the towns of McGrath, Kasigluk, and Barrow.

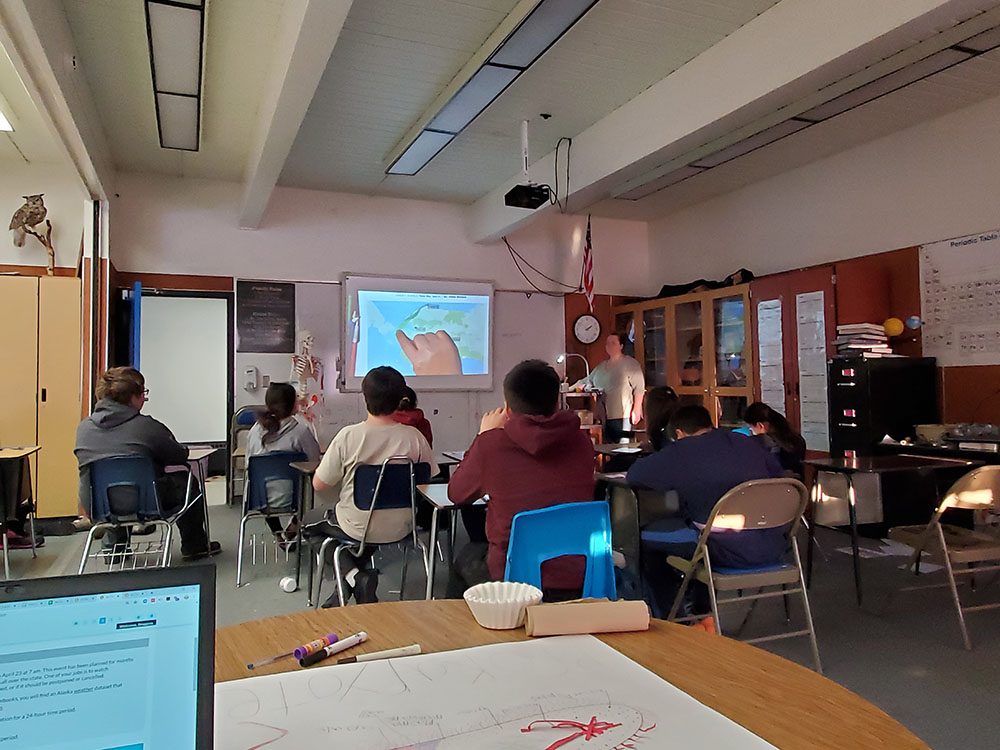

The McGrath School, part of the Iditarod School District, has only 32 students and 4 teachers. With the help of Texas Gail Raymond, a STEM consultant who has been the K-12 Science Coordinator for the Anchorage School District, we were able to work with McGrath teacher Loreé Boggess and her class of 11 students in the 6th, 7th, and 8th grades for almost two weeks—a rare opportunity in a village with no roads going in and out, that’s dependent on small planes, snow machines, and dog sleds for getting around.

The McGrath School is in the Iditarod School District.

The McGrath School has 32 students and 4 teachers for all grades preK-12. The Precipitating Change class was a mixed group of 6th, 7th, and 8th graders.

Coming to a small town and wanting to change the way things have been done can sometimes be problematic. But not in McGrath. “Everyone was glad to see us,” explains Kimball. “We felt welcomed into the group.”

Nathan Kimball emerging from the Alaskan winter.

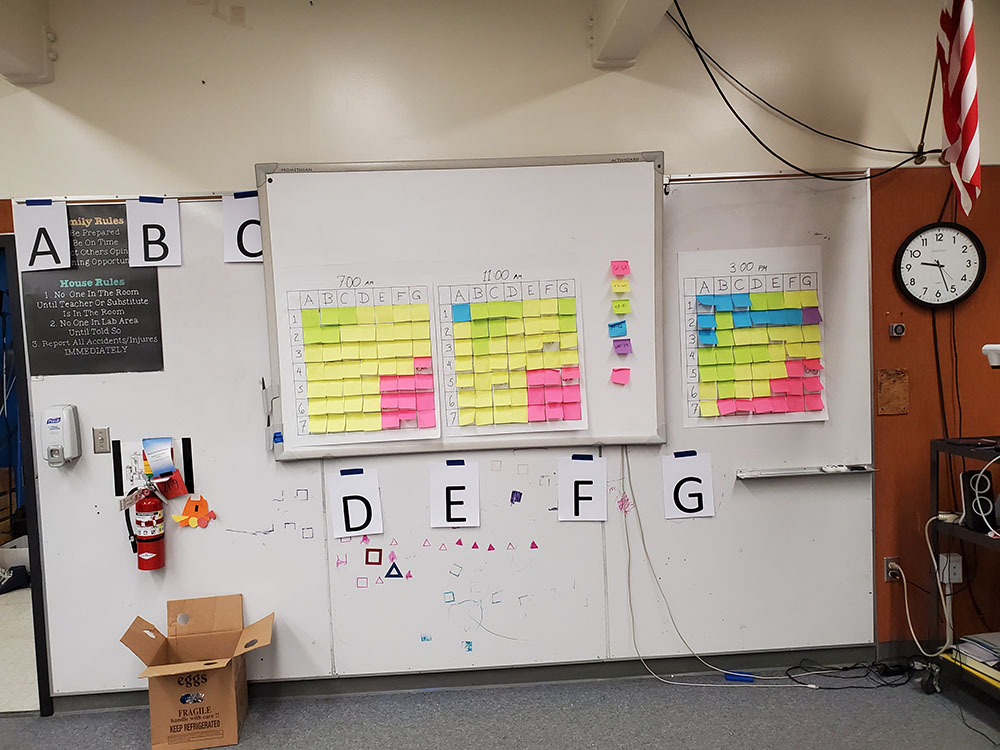

Precipitating Change equips students with iPads to help them take on the role of science expert as they use computational thinking skills to collect and analyze incoming weather data, refine weather models, and make informed predictions. Students also watch videos of people working in the field of weather prediction, including Jackie Purcell, a popular meteorologist for Anchorage’s KTUU television station, and Heather Mace, a bush pilot.

Students track a simulated weather event to learn the basics of weather prediction.

While anything can and will happen in a remote location like McGrath—boxes of equipment stranded by weather, school canceled due to subzero temperatures, small class size, let alone moose wandering through town—Kimball felt that the students experienced the basics of computational thinking. And he has a better sense of what’s hard to do in a small classroom of mixed grades, and what’s easier than one might imagine. For example, students are very comfortable with technology and classrooms are equipped with computers. “Internet is a lifeline there,” Kimball explains. “It’s slow, but not as bad as you might think.”

Moose often wander into town for protection from wolves.

Kimball also learned about one of the essential qualities it takes to live in an isolated place. “The teacher had a lovely way with the kids. In a small town, it’s crucial that everyone gets along. There’s no alternative,” he observes. He’s happy that Precipitating Change was able to fit in.

McGrath is a hub for the famous Iditarod sled dog race, and Kimball got a taste of what it’s like to hurtle through the woods at top speed behind eight spirited dogs, at night, no less. It’s easier for the dogs and their driver to see the trail when it’s bathed in nighttime shadows, versus the daytime, when everything appears uniformly white.

Researchers with Precipitating Change will be returning to work with teachers and students in Kasigluk, in western Alaska, and are continuing work in Barrow, also known by its Iñupiat name, Utqiagvik, located above the Arctic Circle and the largest city on the North Slope of Alaska.