Houston’s downtown flooded after Hurricane Harvey. Florida neighborhoods have struggled with murky standing water after Hurricane Irma. Catastrophe can overwhelm any system, but why doesn’t the ground just absorb the extra water?

In some cases, the answer is a damaged watershed, a concept most people don’t understand, even though we all live in one.

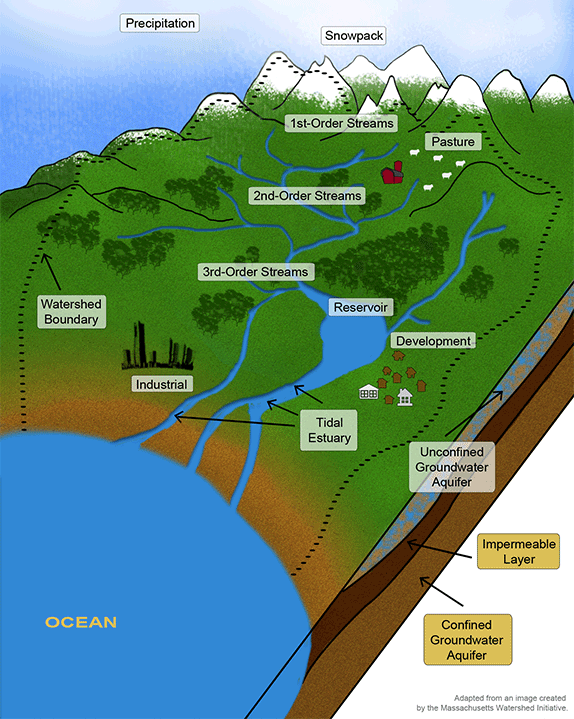

A watershed is the land area where all rain runs downhill to a certain point.

Simply put, a watershed is “all the land area where the rain runs downhill to a certain point,” explains Carolyn Staudt, who leads NSF-funded science projects at the Concord Consortium on land use and its effects on water resources.

Credit: Tony Webster original. CC BY-NC 2.0

Credit: Tony Webster original. CC BY-NC 2.0

A watershed could be described as a naturally occurring traffic cop, efficiently directing water that’s converging from all around to a common location, maybe a lake or the ocean. The water might also be funneled into a deep underground aquifer or be soaked up by trees.

But when the watershed is damaged, gridlock results, water backs up, and flooding occurs.

A wetland or a forest is a good traffic cop. A parking lot or a housing development is not. Once rain hits a paved surface, it has nowhere to go because it can’t be absorbed. Standing water on a sidewalk or a highway is trapped.

Credit: Addison Berry original. CC BY-NC 2.0

Explains Staudt, “Cities have been paving their wetlands,” the very places that naturally absorb water in a flood—or a hurricane. Even a small amount of rain can become a drainage problem where there’s widespread development of wetlands and prairies, which has been the case in Houston, for example.

Why is the connection between land use and water resources important to education?

Read “Part II: Students Learn about Water” to answer that question and find out how some students used the information they learned.