It’s hard to imagine that something so, well, gross could provide such motivation. But that’s just what brought our first Tinker Fellow to our Emeryville, California, office for two weeks this summer. Amy Hammett dove deep into CODAP to investigate data about harmful algal blooms.

The Robert F. Tinker Fellows Program aims to promote innovation, creativity, and cross-disciplinary conversations in educational technology for STEM teaching and learning. Organized as a residency program, the fellowship is intended to bring individuals to the Concord Consortium to spark new ideas, tinker with novel technologies, cultivate outside perspectives, and provide opportunities for reflection on our work.

Check, check, and check. Amy brought all that and more.

Amy Hammett. Photo credit: Maizenews.com. Used with permission.

Her goal: Mobilize a nationwide water monitoring force to collect data about harmful algal blooms and use that data for good. Amy is undaunted by the challenge and gushes, “There are lots of exciting things we can do if we understand the data.”

Before becoming a high school biology teacher in Maize, Kansas, thirteen years ago, Amy worked in data analytics for the healthcare industry. She’s been working to teach other educators how to use local data and let the data guide the curriculum ever since.

Amy’s interest in marrying data analysis and science curriculum emerged at a summit hosted by the National Science Education Leadership Association (NSELA) last year when she recognized that what science educators really need is exemplary, ready-to-use instructional materials. At the time, she had also been collaborating with NSF EPSCoR (Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research) science researchers on place-based problems. She enthuses, “Their primary data is gold for educators and students because it allows us entry into the adventurous world of real science—discovering that which is not yet known!”

That’s just what Amy wants students to do in her science class. She envisions students and teachers using technology to “uncover the unknown and hidden in big data to computationally model those phenomena or systems, and to deploy the resulting model’s predictive power to inform the design of solutions to complex, real-world problems.”

Ask Amy about real-world problems, and she’s quick to say HABs. That’s the shorthand for harmful algal blooms. HABs are defined by NOAA as “colonies of algae—simple photosynthetic organisms that live in the sea and freshwater—[that] grow out of control while producing toxic or harmful effects on people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and birds.” According to the USGS, HABs can modify food webs, alter the taste or quality of seafood or drinking water, and produce cyanotoxins harmful to both water and land organisms, including humans.

Toxic Algae Bloom in Lake Erie.

Toxic Algae Bloom in Lake Erie.

As a teacher, Amy sees beyond the scum. Harmful algal blooms open the door to data-driven inquiry. HABs and their associated problems occur across the country, and thus are of potential interest to many students in many different locales. And because the causes of HABs are a highly complex blend of physical, chemical, biological, hydrological, and meteorological conditions, there are many important unanswered scientific questions around their function and occurrence. In other words, HABs make an ideal launching pad for authentic investigation.

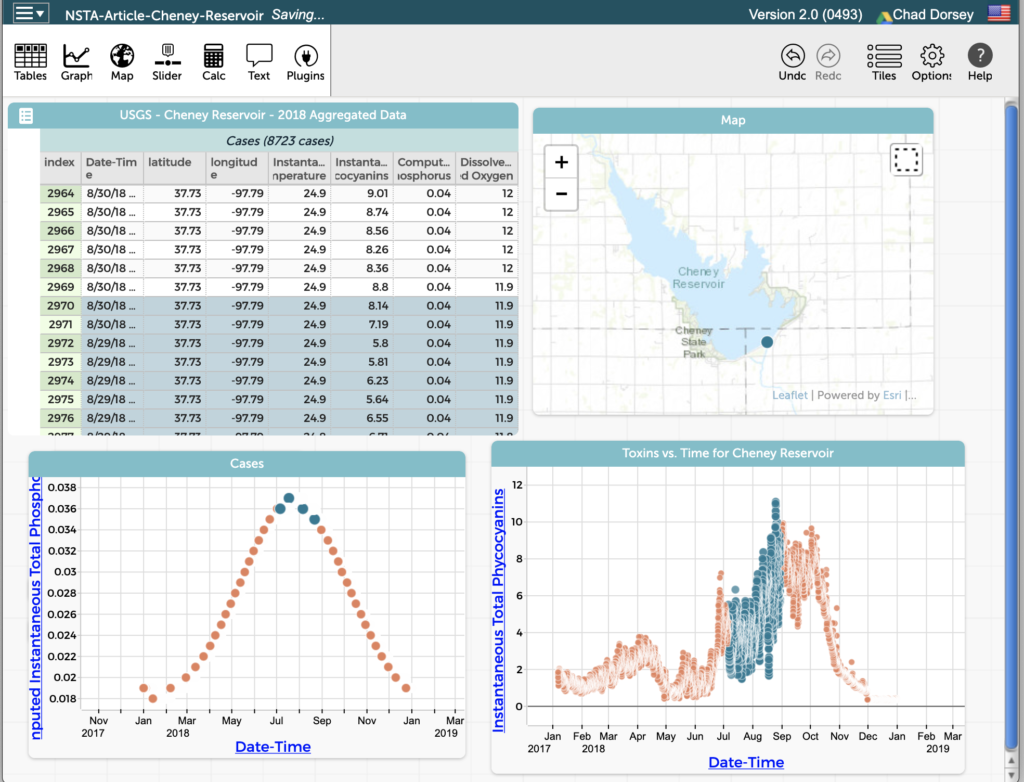

While at the Concord Consortium, Amy conducted her own investigation, exploring HAB data side by side with Bill Finzer, lead developer of CODAP (Common Online Data Analysis Platform). So, what did they find? First, that cleaning the world’s messy, authentic data is an important first step for students, and that new CODAP features could help. Second, a potential new discovery about the trigger for the onset of harmful algal blooms in Amy’s home state emerged.

Using CODAP to overlay two graphs on top of one another, she noticed that the graphs of phosphorus levels and water temperature seemed to match. This “aha” moment led to more research. Digging into the data, she discovered an important causal chain: when water temperature increases, the concentration of dissolved oxygen decreases (a lot!) causing ferric oxide in the sediment to release copious amounts of phosphorus. And that phosphorus is just what algae (and the cyanobacteria living within that makes a harmful algal bloom toxic) need to bloom!

Amy’s incredible data sleuthing has already had an impact. The USGS in Kansas has added two dissolved oxygen sensors to each sampling site, and her colleague Ted Harris at the Kansas Biological Survey is actively researching internal phosphorus loading in freshwater systems in Kansas.

Using CODAP to explore phosphorus and temperature USGS data from Cheney Reservoir in Kansas.

Amy wants everyone to get in on the action of discovery and problem-solving using local data. She has created an investigation for students, using local water supplies as the starting point. There is no prefabricated storyline, though. Instead, teachers are encouraged to use the NGSS crosscutting concepts to lead the way. Using data is key. She says, “The complete story map is not yet drawn; instead, students can co-create one for their own community through data visualization and data storytelling.”

As an outcome of the Tinker Fellowship, teachers and students can use this lesson to engage in investigations of their local water quality using dynamic data exploration. As Amy sees it, “Once students and teachers see the immediate and profound impacts of that kind of real science work and the partnerships that form around it in their communities and regions, there’s no going back.”

Following her action-packed time in California (she also visited the Exploratorium and Muir Woods during her stay), she’s back in Kansas and already out on the Cheney Reservoir with her award-winning Maize Climate Club students, launching the newest version of their data collection sensors. After all, August is “algae prime time.”

Students collecting data from Cheney Reservoir in Kansas.

This fall, Amy will start a doctoral program in Curriculum and Instruction with an emphasis on data science education at Kansas State University. She wants to spread the word about the importance of analyzing data to solve real-world problems—she has a national water monitoring force to marshal.