Imagine that you’re visiting a new city and want to know the best place to get ice cream. You might open your favorite search engine and check out reviews. Or you might see what people on Twitter have to say. Perhaps you decide to search for specific terms and see if more people recommend you try — or avoid — the city’s famous fig ice cream. Depending on the app, these comments might be sorted into categories, such as positive and negative reviews.

But who creates these sorting algorithms, and what skills are needed to make them?

Sorting algorithms are designed to mimic the human brain and are a form of artificial intelligence (AI) whose development is grounded in a strong foundation of the English language. If you are looking for new ways to make English Language Arts (ELA) skills feel even more important and relevant to your students, incorporating such AI into your classrooms could provide the inspiration they need.

The uses and applications of AI are expanding, and the skills needed to lead this development encompass many interdisciplinary skills, including those typically ascribed to ELA classes. Our Narrative Modeling with StoryQ project team — a collaboration of researchers, curriculum and software developers, and high school ELA teachers — has designed an eight-lesson unit that brings AI to ELA students, drawing on both their existing competencies and refining skills critical to ELA courses.

Review sorting, like the ice cream review situation above, falls into the category of “text classification,” a popular use of artificial intelligence. While in theory a person could go through all the reviews one by one and then synthesize the results, using a computer to compile this information is often much more time efficient. Using machine learning, the computer program can even learn to quickly sort new reviews. The trick, however, is to create an accurate program. ELA students are well-positioned for many important aspects of this creation process as the skills commonly taught in ELA classes parallel what is needed to create a text classification program.

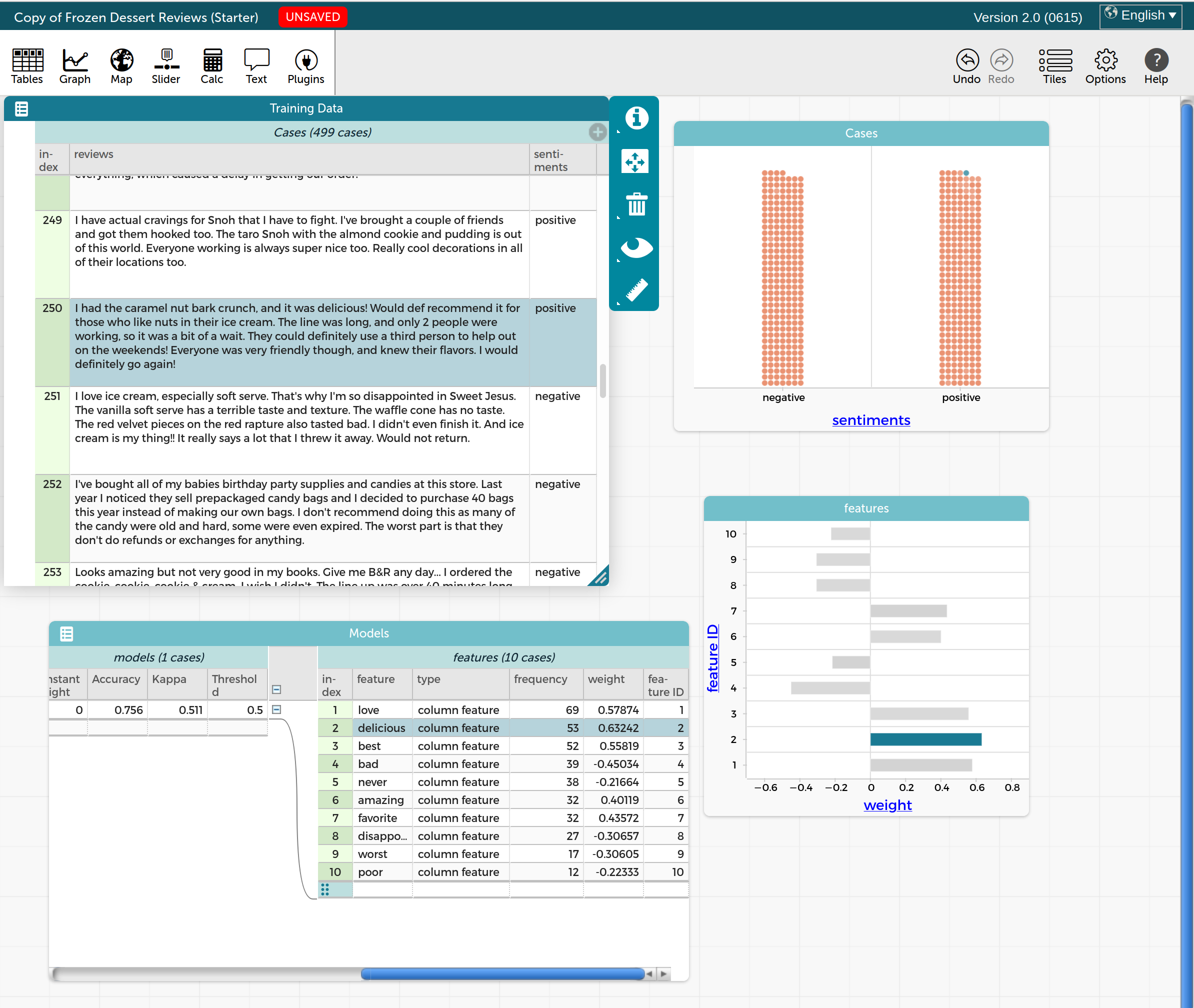

Our StoryQ app is built within CODAP. In this activity, a machine learning algorithm is being trained to identify positive and negative words in sample text.

Our StoryQ app is built within CODAP. In this activity, a machine learning algorithm is being trained to identify positive and negative words in sample text.

Close reading. Developing close reading skills is a critical practice for ELA students. Students are often tasked to consider the tone and theme of passages and interpret pivotal words to make sense of the content. For example, you may ask students to describe what Nora thinks of Patch when she says, “He was abominable…and the most alluring, tortured soul I’d ever met” (Becca Fitzpatrick, Silence). Close reading has a direct counterpart in the field of AI and is critical to the development of text classification models. The success of a model depends on the quality of the data fed to it, which requires skilled readers first to close read and then label the data. For example, to build a review sorting algorithm, developers first need to determine if reviews should be labeled as positive or negative. They need to label statements such as “While the ice cream looked delicious, there was no frozen yogurt. I was led astray!” Labeling data in preparation for model development can be a great application to practice the important skill of close reading (and tone analysis!). Using this context allows students to see the broad consequences of their close reading skill beyond its typical classroom uses.

Diction. Thinking about word choice is important both when students write their own text and when they analyze other texts. Authors are deliberate about their words whether they’re writing fiction, poetry, or informational text. As a teacher, you may ask your students to stop and think about why certain words were used or ask them to highlight the most important words in a passage. Text classification can be a great practice arena for this critical ELA skill. Text classification relies on the computer having appropriate features (words, phrases, etc.) to analyze, and that starts by people “teaching” it what to pay attention to. For example, can a single word — such as “best” or “worst” — be a good enough clue of the reviewer’s evaluation without reading the whole review? What about the phrase “never again”? (Consider this review: “Never again will I go a whole week without getting their moose munch ice cream.”) Asking students to read an initial training set to elicit key features for the computer to extract is an excellent, real-life application that shows students the importance of analyzing diction.

Contextualization. Finally, your ELA students likely spend time considering how words are used differently depending on their context or genre. Text classification provides an excellent test case for this practice. Once an initial classification model is built, certain outputs may be surprising. Analysts then need to search for patterns in the misclassified outputs and determine which features may be leading the computer astray. Such errors can result from words that have multiple meanings or when a word behaves differently depending on its part of speech. Having students seek out the source of these errors provides a real-world application to their understanding of contextualization. As students come up with “rules” to teach the computer how to avoid these misclassifications, they draw on and strengthen their knowledge of the English language.

Teacher praise for the StoryQ module

Twelve ELA teachers participated in our fall 2021 workshop to learn to use the module with their students. Below are just a few of their reactions.

- “It has taken me outside the box in terms of how I could consider teaching language and diction and given me some ideas about the greater context of language.”

- “[It is] a novel topic that would reach students who are more interested in the sciences and tech in general. I think that it is also an authentic use of ELA skills.”

- “I liked the focus on shifting words to change grammar and ambiguity.”

- “I love this activity! I think integrating things like [Activity 3: How Do Humans Classify Text] into class can become very natural and easy.”

If you’re looking for new and relevant ways to engage your students in common ELA practices, AI via text classification may provide the hook. Our hope is that students see the broader implications of the skills they use so frequently in their ELA classes and learn that they can contribute to making AI even more intelligent.

We encourage you to try “Exploring AI in ELA with StoryQ” in your high school ELA classes. Eight lessons lead students through a basic understanding of AI and machine learning using several text classification examples (sorting reviews, determining if a headline is actually clickbait, etc.). With a free teacher account, you’ll also get access to a Teacher Edition of the module with background information, just-in-time teaching tips and tricks, and exemplar answers to embedded questions, plus a “teacher dashboard” that makes it easy to keep track of student progress and provide individualized feedback. Or try the StoryQ app and have students analyze their own data.

Send your questions, comments, and feedback to storyq@concord.org. We’d love to hear from you!