Glaciers form when millions of layers of snow compact themselves into ice. Scientists take samples from glaciers and are able to determine what happened thousands of years ago, just by examining the ice rings. (See the image of an ice core, below, from Wikimedia Commons.)

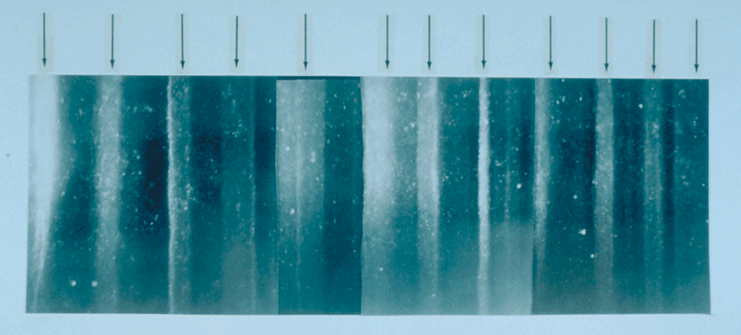

19 cm long section of GISP 2 ice core from 1855 m showing annual layer structure illuminated from below by a fiber optic source. Section contains 11 annual layers with summer layers (arrowed) sandwiched between darker winter layers.

19 cm long section of GISP 2 ice core from 1855 m showing annual layer structure illuminated from below by a fiber optic source. Section contains 11 annual layers with summer layers (arrowed) sandwiched between darker winter layers.

Since snow falls on the top, scientists know that the newest layers are on the top, and the oldest layers are on the bottom. But what happens when the bottom layers aren’t the oldest?

New research in Antartica has shown that new ice was actually being formed at the bottom of the ice sheet as meltwater flowing under the glacier re-froze at the bottom. This poses a problem for scientists hoping to drill ice cores that go back 1.5 million years.

Still, there’s hope to find that really old ice in Antarctica–it’s just going to take more work to find portions of the Antarctic ice sheet that haven’t melted and re-frozen. Instead of working on the slopes of the mountains of East Antarctica, scientists will have to try drilling at the top of the mountains. At temperatures around -50°F and thin air (equivalent to an elevation of 14,000 feet), that’s no easy feat.

But working in these harsh conditions is the only way that scientists might be able to understand what Earth’s climate was like 1.5 million years ago.

http://www.npr.org/2011/03/04/134229249/its-bottoms-up-for-antarctic-ice-sheets