Why Everyone Can and Should be a Scientist

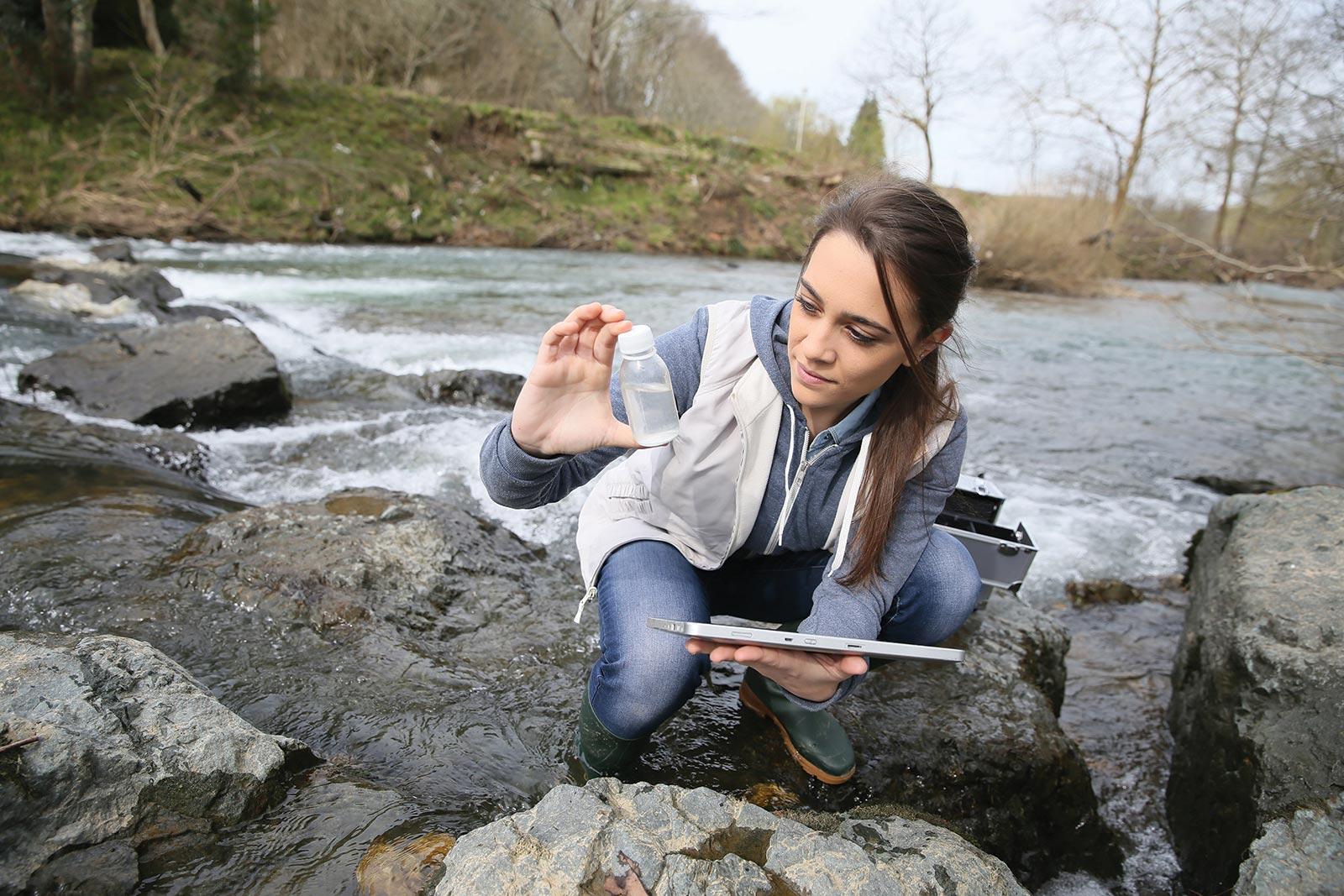

Imagine an eighth grade student climbing down a bank to a creek near her school every day of her summer vacation. She stops at the water’s edge to carefully take a sample in a 5 ml test tube. She analyzes the water along with friends and a few members of a senior center, who have joined her group to gather additional samples. They identify pollutants and add their data to an online database. These data help tell the story of dirty water that needs attention. Restoration work along the creek is under way and, prompted by the data the group has compiled, the city government has begun conducting additional monitoring for sewer leaks and illegal dumps.

Now imagine a pollution meter installed on the roof of an apartment building. Through an RSS feed, an eleventh grade student extracts and analyzes this data. He’s determined to learn more about the causes of pollution. Inspired by his younger sister who plays soccer but has to stay inside when the air is bad, he creates a sculpture that displays the level of particulate matter and shares his artwork—and his data—at a community festival. Regional agencies have expressed interest in the data collected by this rooftop pollution meter to assess the impacts of traffic, weather, and fire on community health.

These are examples of citizen and community science (CCS), and the data collected and contributed by young and old, amateur and veteran, are critical. These data create a mutual dependence that makes CCS both scalable and meaningful; scientists benefit from data that would be difficult or expensive to collect, and students benefit by learning with scientists and contributing to authentic scientific work. CCS is more than “realistic” science, it is real science—a difference that has emotional, motivational, and cognitive consequences.

CCS encompasses many forms of science in which members of the public participate in the production of new knowledge used for resource management, community decision-making, or basic research. In contributory or scientist-led projects, a professional scientist has a specific question to answer and defined protocol to follow. These are typically known as citizen science projects. Co-created or student-originated projects start from a question or problem learners have identified. Such projects are more commonly thought of as community science. There is a wide spectrum of CCS projects with many degrees of collaboration and contribution.

Authentic science and identity

An emerging set of digital tools for producing, sharing, and analyzing data is now available for educational use. These can support the Next Generation Science Standards, which highlight the importance of authentic science and engineering practices, including asking questions and defining problems; planning and carrying out investigations; analyzing and interpreting data; and obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information. However, the development of scientific identities is equally important. Participation in authentic science can support the development of scientific identities by exposing learners to other critical aspects of science, including scientists’ ways of communicating and thinking and a wide variety of careers and mentors in science. It also shows learners that science can serve many purposes, including those relevant to their communities. CCS can help develop learner agency by supporting engagement with unanswered, often messy, questions, and contributing to endeavors that extend beyond a report card.

Best practices for learning in CCS

The two ways of working with data described above—from direct water samples at a local creek to data collected from a rooftop pollution meter—are both possible in CCS thanks to tiny digital temperature sensors, real-time graphing, new Internet of Things sensors, collaborative digital sharing tools, and low-cost electronics. Of course, much can still be done with a clipboard and pencil. Across various forms and technologies, research has documented best practices for the most educational value from youth participation in CCS.

Support specialization

Science is done in teams, by team members with different levels and kinds of knowledge and experience. In CCS, some participants may take on more or different kinds of work than others. As they develop roles within a project, participants can see all parts of the process, even while they might specialize in particular aspects of scientific work—from conducting data analysis to checking data quality or designing materials for dissemination. These roles can help young people, especially those who are new to science, use existing identities and build from areas of expertise toward other practices of science.

Make scientific contributors visible

It is also important to make both professional and non-professional scientists visible by creating a direct connection to scientists, while acknowledging young people as legitimate contributors and local experts. To ensure that learners see that their work is valuable to others, students and citizens should have opportunities to present data and findings, from posters at scientific conferences to presentations at a town hall or research briefs on a community forum. Scientists should also ensure that participants understand how their data is being used to create new knowledge.

Create conversations

In both CCS and more traditional science education, young people often have few ways to share their ideas and expertise. CCS projects can go beyond scientific products and help participants share their work with family and friends in ways that feel relevant and exciting.Media and messages should encourage personal expression alongside scientific evidence.

Make a big deal of data

Data is the currency of science, and tools for producing, storing, accessing, and analyzing data make participation by all more powerful. Producing data is core to CCS, yet many projects move quickly to analysis and explanation as the focus of student reasoning. Conversations in the field and lab can bring to the surface questions about what counts as good data and how to describe the data for others who are looking at it secondhand. Creating datasets that capture observations and allow learners to answer local questions goes beyond formal protocols.

Provide opportunities for learner action

Connecting science to concerns, curiosities, and larger communities makes CCS meaningful. From organizing events to using research findings to advocate for policies to participating in restoration or other actions informed by the data, connecting CCS activities to local issues is critical when considering both the equity and ethics of science and science education. CCS is one small step to ensuring that science is accessible to all and reflects the questions and concerns of many.

Community and citizen science is more important than ever as a way to address climate change, species collapse, changing land uses, and other local and global concerns. CCS makes it clear that science is a collective endeavor, and that doing science is vital—and possible—for everyone.

Colin Dixon (cdixon@concord.org) is a research associate.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant DRL-1640054. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.