This series details the eclipse-chasing exploits of our President and CEO, Chad Dorsey, as he heads down to Tennessee on a quest for the total solar eclipse. See the whole series.

Packing for the 2017 Great American Eclipse is amazingly simple, especially considering the laboriousness of prior eclipse-chasing quests. For one, it’s possible to drive there, something generally unthinkable with most eclipses. That is, it’s pretty much never the case except in this particular instance that the word “eclipse” ends up in the same sentence as the words “road trip!” More about that later. Second, it’s in a highly populated area with significant infrastructure. This has notable implications, both potentially good and potentially problematic, as we’ll see.

First, the potentially good. The key rule in chasing any eclipse is very simple: make sure you see it. However, as simple as it is to state, actually adhering to that rule is anything but simple. Because in order to see an eclipse, you need to be able to see the sun, which means there can’t be any clouds. The forecasts for Tennessee look pretty good for this right now, and clear skies seem like a simple thing to ask for in the summer, until you start to think about it a bit more.

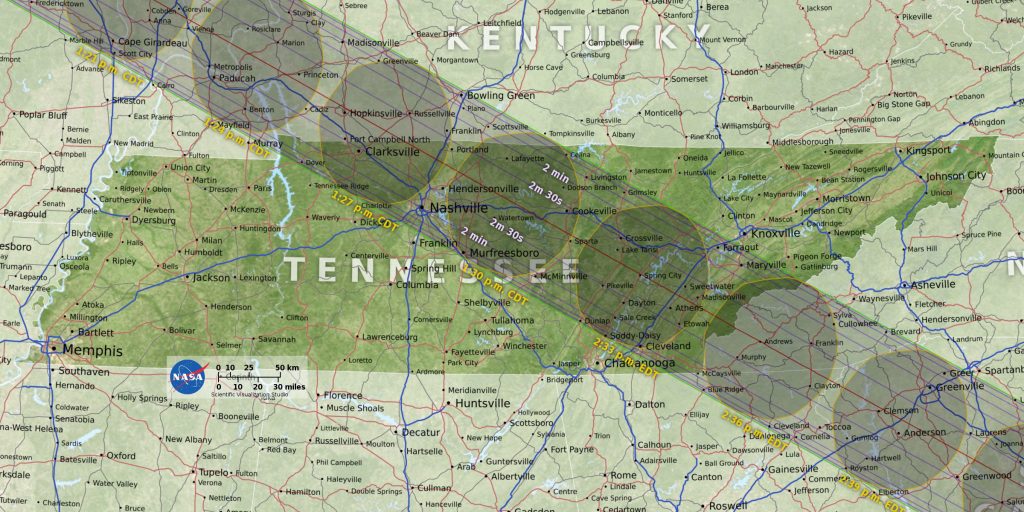

For one, even if it’s a generally clear day, the warmth of the air in the summertime leads to convective patterns that cause the buildup of thunderstorms. These thunderstorms occur as the ground has had time to warm the air above it, a process that usually ensures that thunderstorms occur in the early afternoon. Of course, the eclipse in Tennessee will occur at around 2:30 Eastern time—an ideal time for thunderstorms to occur. So, as is always the case in eclipse chasing, we can by no means count on clear skies as a sure thing.

The thunderstorm, Tez Goodyer. CC BY-ND 2.0. No changes were made.

If thunderstorms do seem ready to occur, or if the sky is overcast or filled with large clouds, die-hard eclipse chasers will shift to their Plan B — scouting out new locations in the day or hours before the eclipse—with a desire to get somewhere, anywhere, under the moon’s shadow where the phenomenon can be fully seen. In this year’s case, doing this is markedly easier than it is for many other eclipses, given that the US highway system provides an ideal means of relocating vehicles and people.

In considering this all, I’ve been keeping a close eye on two things. First, the weather reports. While definitive weather reports aren’t released yet for eclipse day, the historical weather charts and the time of the eclipse make it clear that it’s possible there will be thunderstorms in Tennessee on eclipse day. Second, mobility on the day of an eclipse—this can make the pivotal difference between standing under the marvel of totality and simply looking at clouds in a darkened sky.

Which brings us to the other thing that’s potentially negative. That one is a Catch-22. The roads that bring easy accessibility of the eclipse make it a goal for many Americans to seek out. Because of this, however, many assumptions project that main travel arteries will be filled. That’s a major problem—a large percentage of the millions of people who are expected to be traveling toward the path of totality are expected to be driving on the Interstate system. This holds a real potential for dragging major roads to a crawl even before totality hits. At the point of totality itself, it’s expected that many drivers will stop outright in the middle of the road to get out and stare.

So even those with a very solid location for eclipse viewing need to plan for the worst. As I look over the maps, I’ve begun plotting out possible scenarios on the smaller roads in the region, drawing in the path of totality across our road atlas in pencil and examining side roads, underpasses and bridges. The key consideration is how we might go about both chasing blue skies and avoiding crowds—if conditions make it necessary to head out on the move.