The Concord Consortium celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. This milestone occasion coincides with another notable event: ten years ago Chad Dorsey became only the second President and CEO in the organization’s history. He followed in the footsteps of our founder, Bob Tinker, who, like Chad, was a physicist.

The Concord Consortium celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. This milestone occasion coincides with another notable event: ten years ago Chad Dorsey became only the second President and CEO in the organization’s history. He followed in the footsteps of our founder, Bob Tinker, who, like Chad, was a physicist.

“The ability to ask interesting questions about the world is one that comes pretty naturally to physicists,” explains Chad, who is fascinated by the ordinary and yet mysterious conundrums of everyday life. Recently, he mused about an everyday phenomenon he had discovered in the kitchen—two almost identical pieces of chocolate (but with different cacao percentages) sounded with two different tones when dropped on the counter. This particular idiosyncratic question may enchant him because he’s played the violin since long before he was an undergraduate at musically renowned St. Olaf College.

“Moving to Massachusetts has marked the first time since fifth grade that I haven’t played in an orchestra,” he laments.

That’s because his days are filled instead with orchestrating a 45-person organization brimming with some of the most creative people working in science education. He first learned about the Concord Consortium when he was leading national and statewide professional development workshops for the Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance (MMSA), where he developed technology-based assessment materials for teachers and worked with AAAS Project 2061 to provide guidance for teachers on using digital phenomena and representations in the classroom.

“I stumbled across this amazing organization doing things that were a level above anything else out there,” he explains. It reminded him of the research he’d done as a graduate student in physics at the University of Oregon modeling systems and creating simulations using technology. “It was clear that the same kind of thought and energy was going into the work that the Concord Consortium was doing for education.”

He subsequently collaborated with the Concord Consortium on GENIQUEST, a precursor to a number of highly innovative projects that explore heredity and genetics by allowing students to breed virtual dragons and examine patterns in their offspring, traits, and genes. “There were a lot of ways in which Concord jibed with my view of the world—using technology as a way to open up the world for students.” Chad is now Principal Investigator (PI) or Co-PI on a diverse range of National Science Foundation-funded programs at the Concord Consortium, including those exploring data science education, collaborative learning in mathematics, inquiry-based science learning, and genetics.

But he’s adamant that technology is not a substitute for teachers. “Every time Concord approaches something, we do it with a teacher’s hat on and with an eye to providing students a path to experience and understand the phenomena of the world in a new way.”

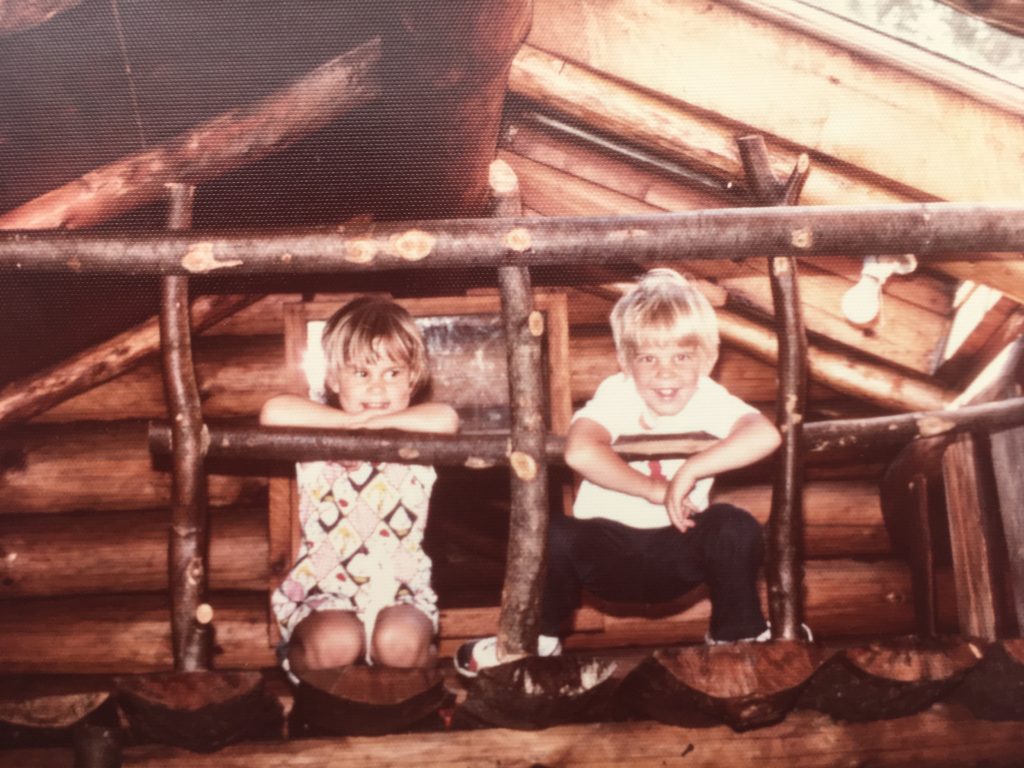

He wants to awaken the “inner scientist” in everyone, not just students. His own upbringing was a template for igniting a child’s curiosity. His mother was an elementary school teacher and his father taught physics in middle and high school. His summers were spent at an 800-acre Audubon camp in Wisconsin, where he and his parents lived in a log cabin built in the 1800s.

The log cabin at a Wisconsin Audubon camp where Chad spent his childhood summers.

The log cabin at a Wisconsin Audubon camp where Chad spent his childhood summers.

“It was all about birds and nature,” he explains, sounding as if he can’t believe he was so lucky. “People were constantly explaining the world around us and thinking about how to make new experiences happen.” His days might include observing a monarch butterfly break out of its chrysalis in the centerpiece of a dinner table or stopping lunch in its tracks as everyone ran outside to watch a hawk soar overhead. During those summers, life everywhere was full of demonstrations, experiments, and wandering in the woods, prairie, or lakes on the camp property. “I experienced the world by exploring it.”

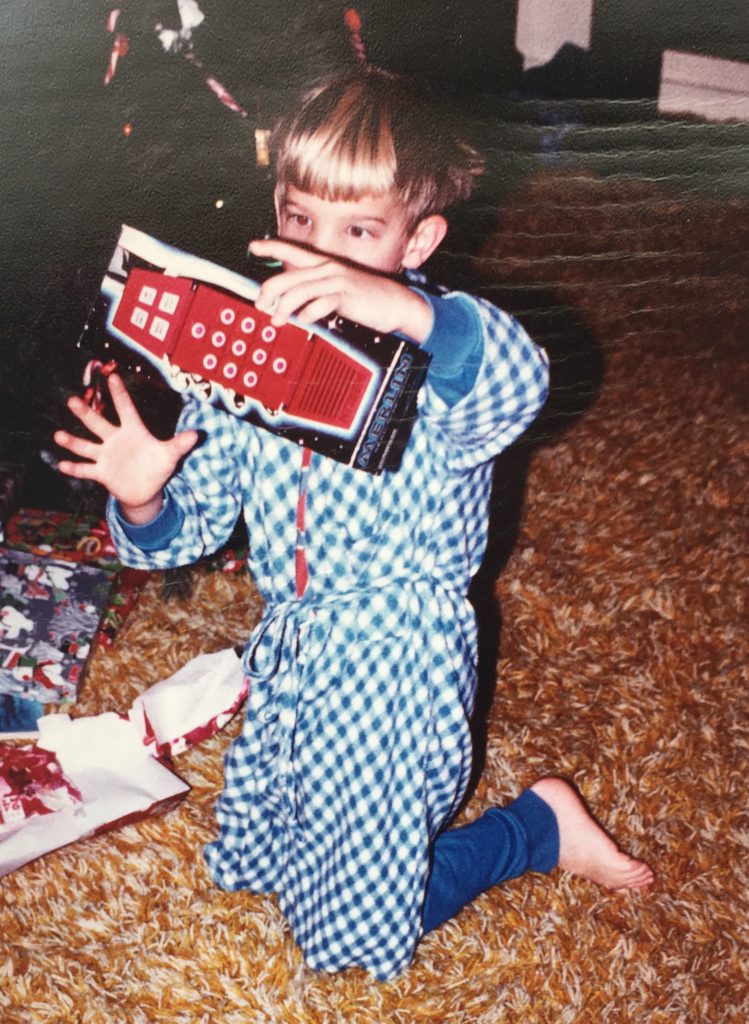

Chad’s excitement about technology was evident from an early age.

Chad’s excitement about technology was evident from an early age.

Chad’s first computer was an Apple ][e that his father brought home from school when Chad was 12 years old. Little did he know then, but the die had been cast. “We always had computers earlier than many folks in the neighborhood because of my dad’s connection with education,” explains Chad. Eventually he finished the coursework for a Ph.D. in physics at the University of Oregon, but not before realizing he cared more about the teaching than “being locked in a research lab.”

But inquiry-based teaching is a challenge equal to any. “It takes a real combination of art, experience, knowledge, and then patience to be able to guide a learner along a path that helps them discover something new about the world,” he says. “It takes great confidence as a teacher—and as an education system—to be able to step back and not give the answer or step in when students are fumbling with unfamiliar concepts. You don’t always know exactly what will happen, but you know there will be new learning that will come out of it.”

He’s always been excited by unlocking and explaining the mysteries of science and engineering, but he regrets that the number of times students get to experience real science in the classroom is limited.

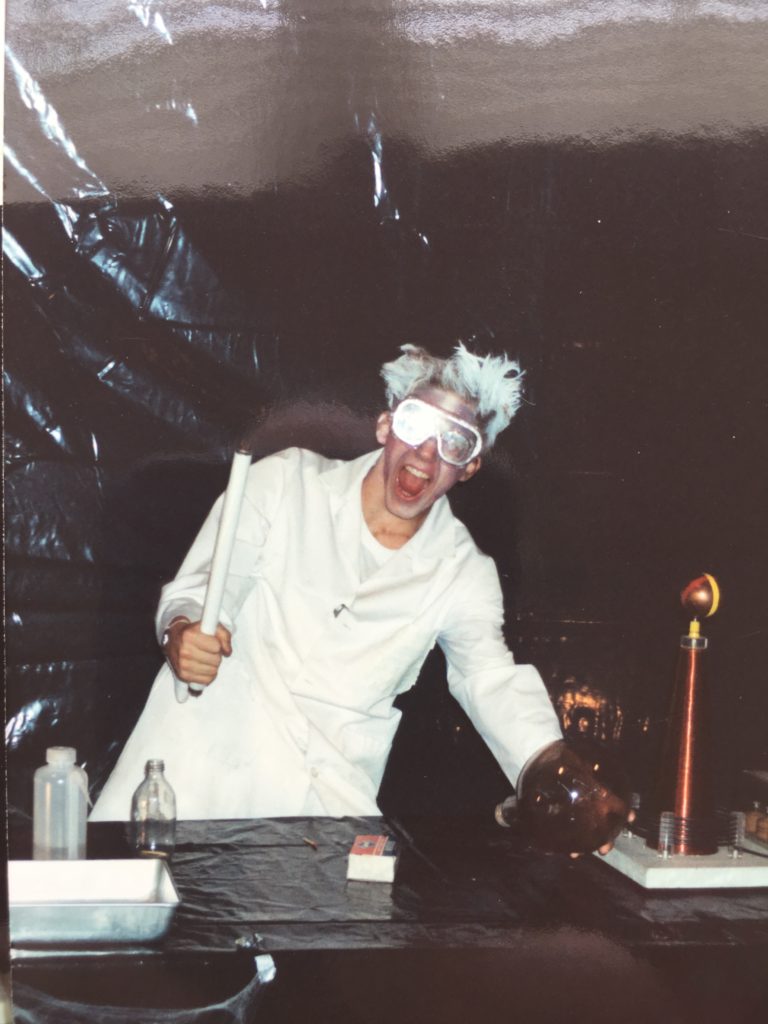

Chad as a mad scientist at Halloween, though he “fully recognizes that scientists don’t look like that!” (This is what a scientist looks like.)

Chad as a mad scientist at Halloween, though he “fully recognizes that scientists don’t look like that!” (This is what a scientist looks like.)

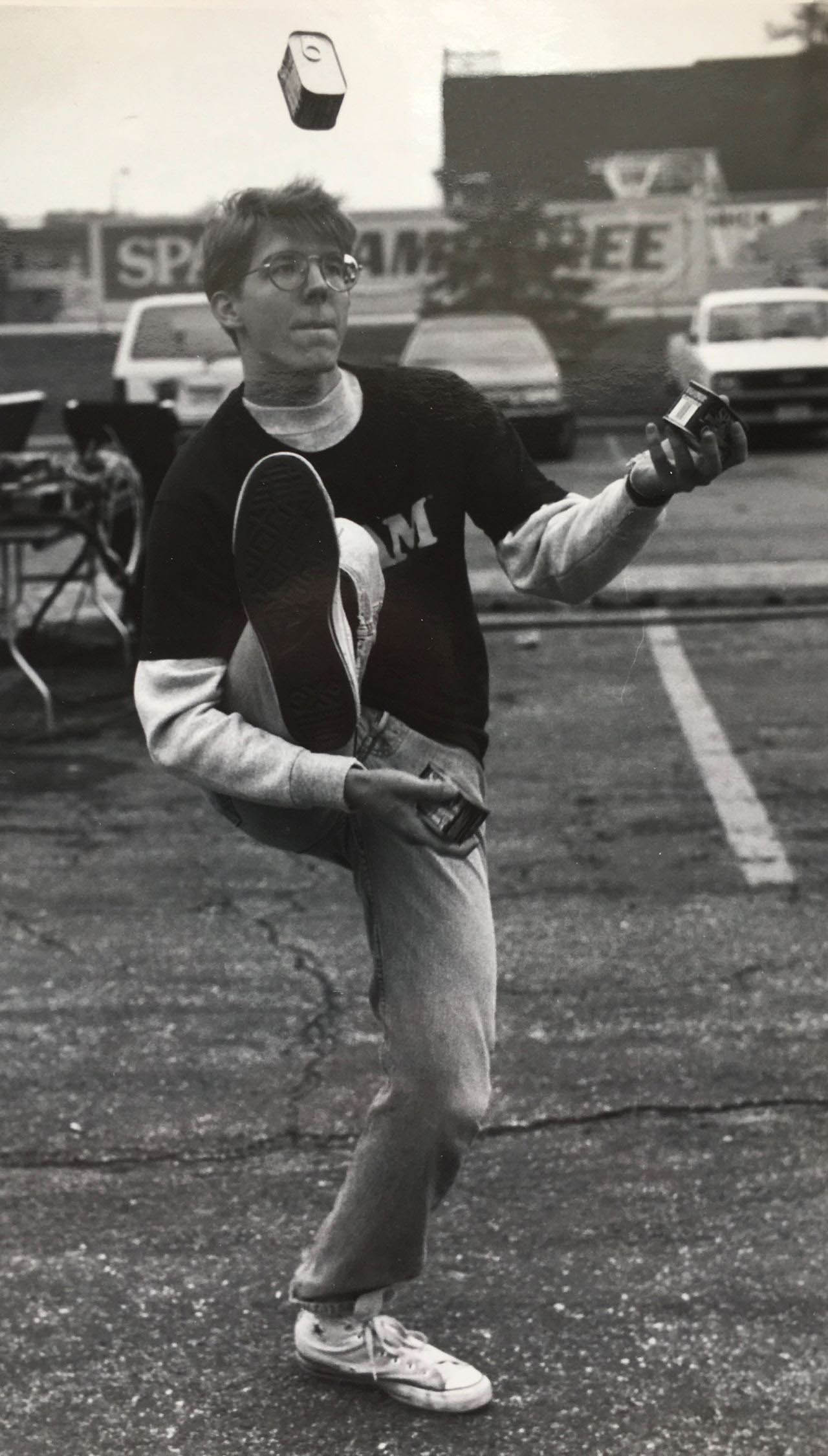

Chad juggling cans of Spam at the Spam Jamboree in Austin, MN.

Chad juggling cans of Spam at the Spam Jamboree in Austin, MN.

“We all start out absorbed by the world around us. But somehow our system of education manages to drum that inclination out of students by age 14, if not earlier. I don’t think that happens because we don’t want students to experience the wonders of the world. But when you’re dealing with a classroom of 30 students, the mechanics of education often simply become prohibitive. A lot of what we are aiming for at the Concord Consortium is to bring real science and classroom science much, much closer together. At the core of what we’re trying to do is giving students the experience of being scientists so that they recognize that they can ask and answer questions of their own.”

So what does he think the future has to offer education? Some of his top picks are AI, voice and speech recognition, and collaboration tools, all areas that the Concord Consortium has begun to address. “Going forward, there’s no question that artificial intelligence is one of the things that we know that we don’t yet fully understand, both as a society and in our work at Concord,” he says. “There’s also exciting new work being done around how technology can help collaboration, in the classroom and for student assessment—I think that’s something that may not be on people’s radar.”

Another is advances in voice and speech data, even though Amazon Echo and Google Home seem more intelligent than they are. “If you learn to speak their language it feels like they’re capturing everything,” he says skeptically, but capturing a noisy classroom filled with teenage voices speaking in colloquial language is something quite different and more difficult. He’s been working on a pilot project with SRI International, the University of Texas at Dallas, and others to raise awareness about what can work and what’s possible in applying speech technologies to education. “If we could tackle just a few important issues and pool the information we collect, it would revolutionize education research.”

He says we all know what technology will be like in ten years: lighter and faster. “It is always going to be better and there always will be something new,” he says, admitting that he sounds a bit glib. For the Concord Consortium, he says more seriously, the challenge is remaining focused on its core mission of leveraging the best technology for learning.

Chad and an eclipse-chasing group of family and friends in 2017.

With so much technology in the world (and at home), do his own two children balance science with the liberal arts, as he did? “I try to let things happen and not push anything on them,” he explains. “They’re definitely interested in exploring the world, and I think that may come from the fact that we haven’t squashed that curiosity out of them, but rather encourage it whenever it appears.” His family also seeks out non-technology adventures like hiking in Iceland (“the best example of traveling to another planet this planet has to offer”), attending the Mummers festival in Philadelphia, and chasing an eclipse.

Among the reports, gizmos, and grant applications on Chad’s desk is a picture of an orchestra conductor. “There’s nothing like sitting in the middle of an orchestra and playing a symphonic work,” he says wistfully. Leading an orchestra and leading an organization have much in common. “You have to help a group move forward without being in control of all the individual actions,” he explains. “Being part of a collaborative group has been shown to raise the level of cognition present. In some ways you have a larger collective ability to hold ideas, imagine, and think through a problem when working together than if you are just one or two people.”