Engaging Multiple Perspectives in Alaskan and Hawaiian Classrooms

Precipitating Change with Alaskan and Hawaiian Schools is a National Science Foundation-funded project with partners from Alaskan and Hawaiian Native communities, multiple universities, and the Concord Consortium. Together, we are exploring approaches to designing, testing, and refining multi-perspective, middle school science instruction about coasts and coastal change.

Coastal regions in Alaska and Hawai’i have always experienced change, but recently the speed and intensity of change has been increasing in response to human development and climate change. In Indigenous communities, where people have longstanding cultural connections with place and rely on subsistence practices of hunting, fishing, and gathering traditional foods from the land and ocean, changes to the coast are relevant to many students’ lives. Investigating coasts and coastal change can involve employing both Indigenous and Eurocentric science approaches, as well as diving into re- lated areas, including history, culture, and community decision-making.

Exploring and valuing multiple ways of knowing

Indigenous children represent a significant portion of school populations in Alaska and Hawai’i, but Native students often experience science class as disconnected from their communities’ cultures and ways of knowing. Thus, instruction concerning coasts and coastal change in Alaska and Hawai’i calls for a multi-perspective approach.

As we work together to understand approaches to and implications of enacting multi-perspective instructional activities, we are actively grappling with some fundamental questions:

- How can multiple perspectives be appropriately included in instruction in ways that equitably demonstrate respect and value, rather than some perspectives being represented in deep ways while others are represented in shallow ways?

- What does “learning” look like when it authentically represents multiple perspectives?

To better meet teachers’ and students’ needs and to engage students more authentically with multiple perspectives, we are currently redesigning the project’s curriculum.

Below is a description of the unit piloted by seven teachers in 2022-23. The unit drew on Cajete’s Creative Process Instructional Model* as a foundation for designing culturally congruent instruction. The four-lesson unit utilizes Universal Design for Learning (UDL) elements such as a multiple-representation glossary and translations into local languages, including Hawaiian, Marshallese, Yugtun, and Alutiiq. We are also working to align the unit with the cultural education standards in both states.

Lesson 1: Encountering First Insights provides a coastal Indigenous cultural experience (Figure 1). Students explore memories and different relationships that community members (including Elders and families) hold with their coastline. Students also begin a community education project where they can deepen their own relationships with their place, share what they learn, and contribute to community preparations for changes to their coasts in the future.

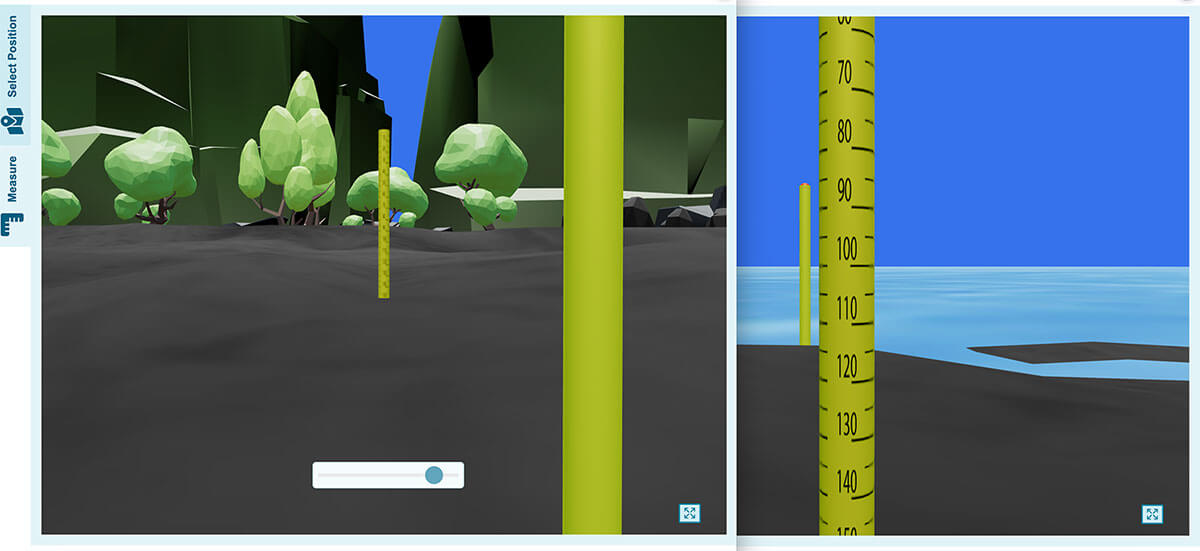

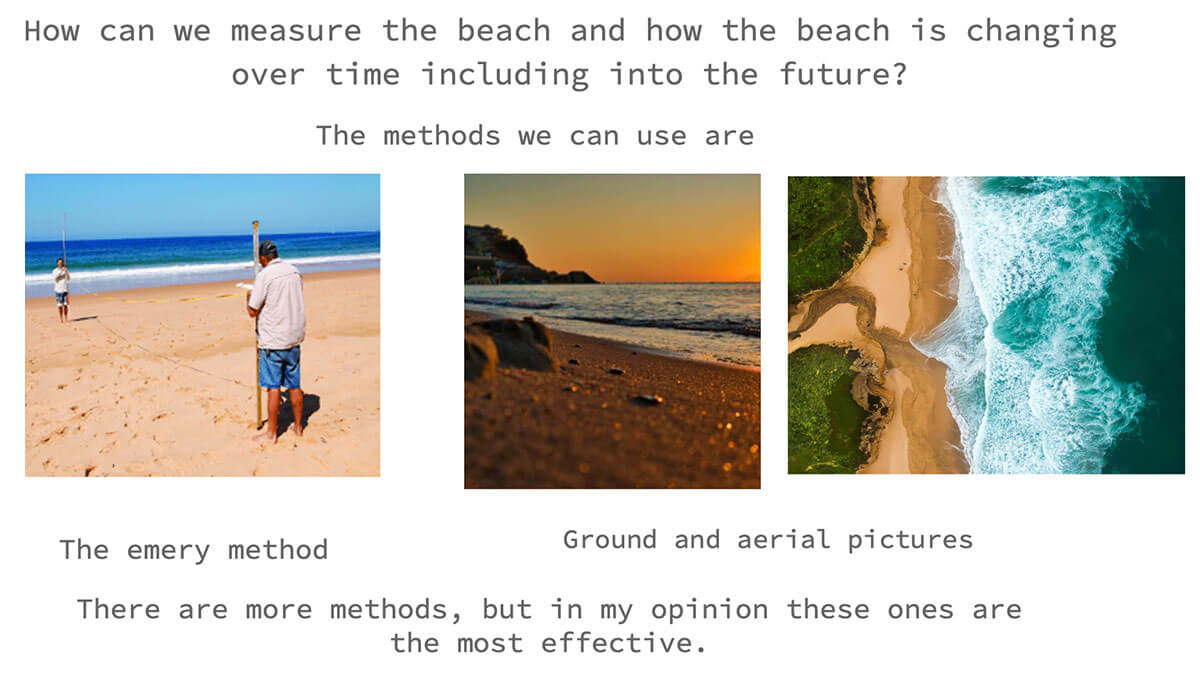

Lesson 2: Preparing and Immersing introduces Eurocentric approaches to monitoring and modeling what is happening along the coast. Students explore ways to measure their beach to figure out how it might be changing over time (Figure 2). Students use data they collect to create a graph and compare their data with measurements from a decade ago.They build both cardboard 3D and digital 2D models using their data.They turn their classroom into a coastline replica and work in teams to create a beach profile using a computer simulation (Figure 3). Finally, they consider different ways of monitoring their beaches and reflect on how multiple approaches can promote understanding.

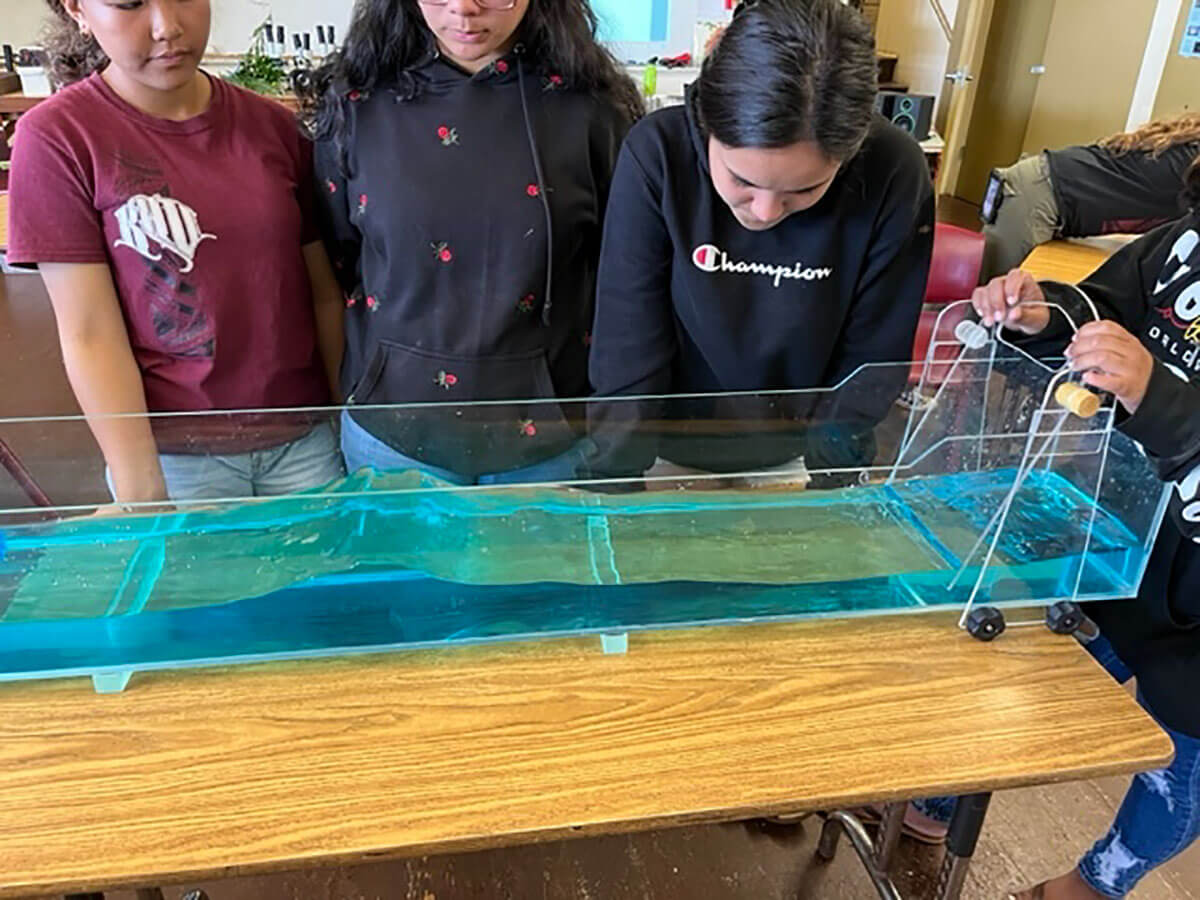

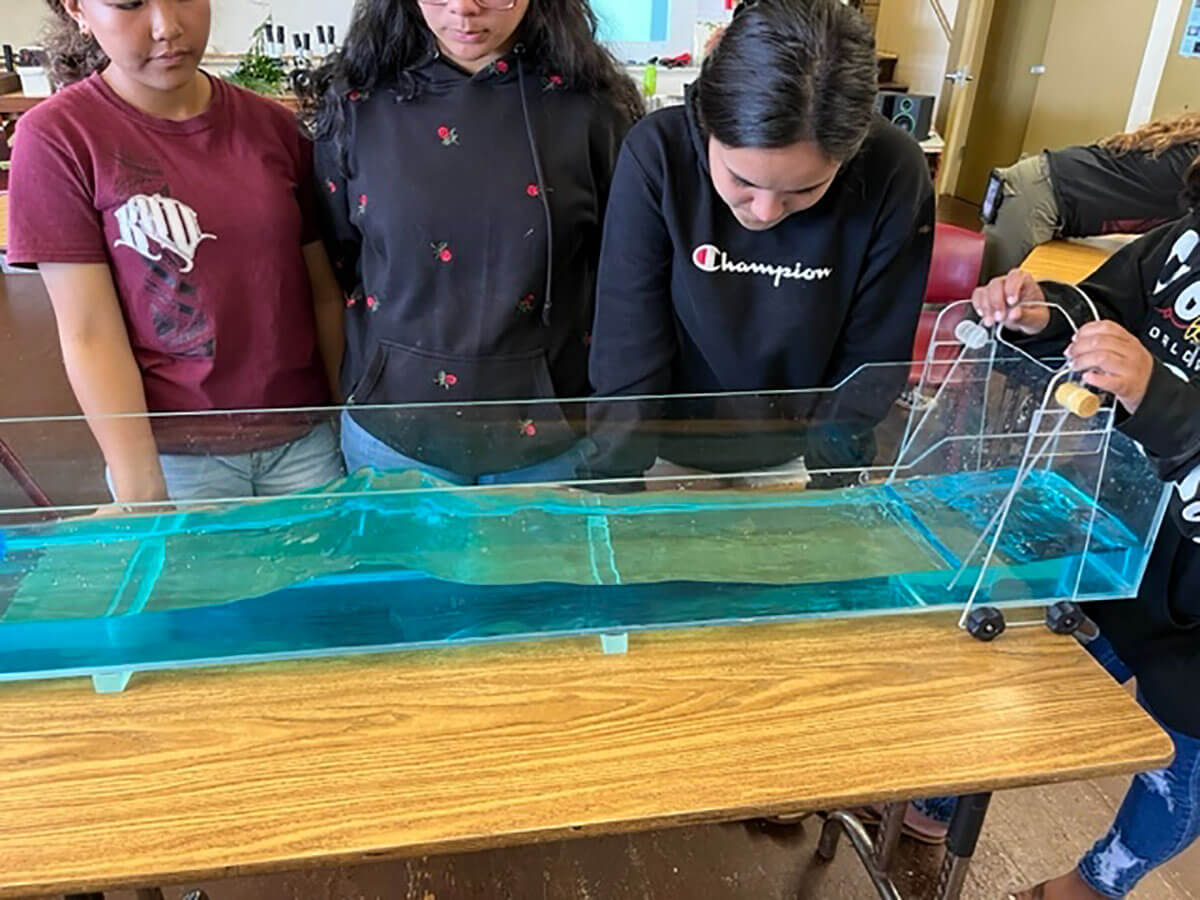

Lesson 3: Inventing and Creating invites students to dig deeper through investigation, exploration, art, stories, experimentation, and modeling while drawing on multiple perspectives. Students explore what causes a beach to change over time. They investigate waves using computer models and a table-size model wave tank (Figure 4). Beaches change largely because of the action of waves, and students model wave action in the tank to investigate how waves may impact their beach. They connect local stories they hear and remember, and share ways of examining how events occur in the past and present.

Lesson 4: Evaluating supports students in enacting written and spoken learning performances. Students consider different adaptations that other communities have made to protect their beaches and interview people in their community to see what, if anything, community members think should be done about local coastal change. They work on a community education project designed to contribute to their community’s understand- ing of what’s happening on their coastline (Figure 5). Finally, students share their project with their class, with other students across the two states, and with their families and communities.

Classroom context

During a recent visit to the Hawaiian partner schools, we witnessed students engaging with their own ways of knowing their beaches. One young girl stayed after class to explore the wave tank and told us stories about going to the local beach to fish with her grandfather on weekends.

Teachers are noticing changes in student engagement. One teacher in Hawai’i noted, “What motivated and engaged my students was the opportunity to communicate their own personal/familial experiences and opinions about a location that was personal to them. Communicating about a location that is tangible and familiar affords them a feeling of success and valuable contribution in the classroom setting. For some students, this has even allowed them a rare or first-time opportunity to access classroom learning in a meaningful way.”

A teacher in Alaska told us, “What engaged my students was the multitude of hands-on learning opportunities. The work outdoors, the wave tank, and the drawings of their beach were all assignments that motivated them the most because they were able to put their own words and experiences into science, rather than trying to fit themselves into a pre-scripted science curriculum. This goes beyond place-based learning and implements student- based learning.”

We are excited to continue learning and working with Alaskan and Hawaiian communities, and look forward to ongoing collaboration with our many partners to develop culturally appropriate approaches to exploring coasts with middle school students.

* Cajete, G. (1999). Igniting the sparkle: An indigenous science education model. Kivaki Press.

Carolyn Staudt (cstaudt@concord.org) is a senior scientist.

Beth Covitt (Beth.Covitt@mso.umt.edu) is a science education researcher at the University of Montana.

Noelani Puniwai (npuniwai@hawaii.edu) is an Associate Professor at the University of Hawaii.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant DRL-2101198. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.