Teacher Innovator Interview: Julia Wilson

High school chemistry teacher Portsmouth, Rhode Island

Julia Wilson knows that her 10th grade chemistry students wonder, “Why am I sitting in this classroom counting atoms on a worksheet?” But she is optimistic that she can help them see the purpose in science. Online resources and a new approach to labs are helping expand her students’ knowledge.

Julia, who teaches at Portsmouth High School, laughs, “It’s very odd to be teaching where I grew up.” Chemistry is the “central science” at the physics first school, tucked between physics in 9th grade and biology in 11th. According to Julia, chemistry is a gray area for students. “Kids understand physics in everyday life and they understand the biology of what they’re living, breathing, experiencing.” Her goal is to build bridges between those two subjects and help students see the importance of chemistry for explaining the world.

Julia is a research participant in our National Science Foundation-funded InquirySpace project, which offers tools and a curriculum sequence that guides students through conducting open-ended investigations. She admits, however, that when she tried to simply pop an InquirySpace activity into her class, it failed. Reflecting on the experience, she says, “I was trying to make inquiry look like a traditional lab.” Julia now focuses on providing supports for her students while letting them figure things out on their own.

Passionate about teaching, Julia describes her path to the classroom as non-traditional. With several medical professionals in her family, she mapped a pre-med route, majoring in biology and working as an EMT at Bates College. But it was there that she realized she wanted to teach. Although she took some education classes, she did not have the traditional teaching credentials when she graduated, so she signed up with Teach for America. After a six-week summer preparation program, she was assigned to a school in St. Louis where she taught geometry for a semester then chemistry for a year and a half.

When she moved back to the East Coast to be closer to family, she was hired as the inaugural chemistry teacher at a new charter school in Lynn, Massachusetts, and had the opportunity to design the curriculum. But it was a physics class that changed Julia’s classroom practices. She recalls, “There were so many opportunities to let kids play with things.” For example, she gave students a ping pong ball and a meter stick and had them prove Newton’s Second Law. “That shifted my thinking about what science could look like and what students are capable of doing.”

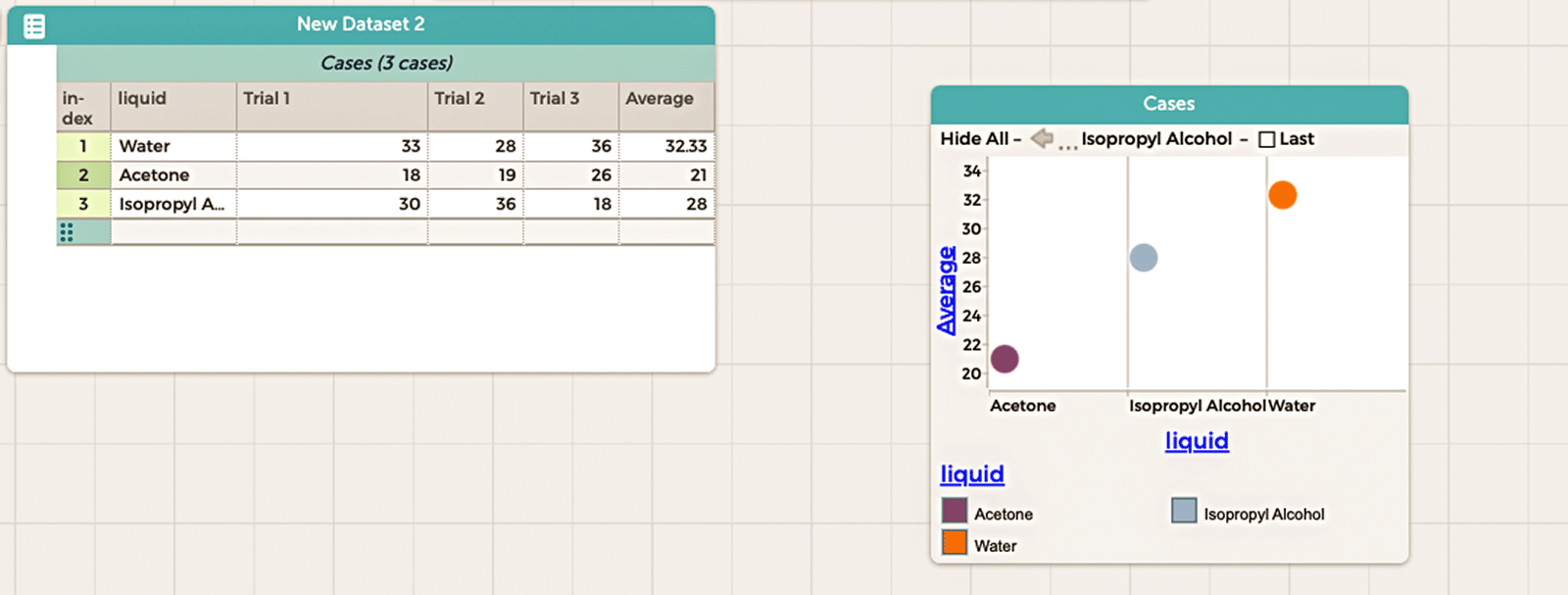

In Portsmouth, Julia now strives to teach chemistry through that same lens. The InquirySpace curriculum units are aligned with this approach, each focusing on a driving question, such as “Why do I feel cold after getting soaked with water, even on a hot day?” When her students recently completed this unit, Julia was thrilled that they were able to apply the same scientific concepts to a new context when she asked them why ice keeps their soda cold.

She also credits the Next Generation Science Standards for shaping what science can look like, though she believes teachers need support in implementing inquiry while achieving content standards. In her own classroom, she aims for that “sweet spot between content and inquiry,” working to transform otherwise cookie cutter labs into inquiry-based opportunities. For instance, she gives students vinegar and baking soda to investigate the conservation of mass. “Here are your materials,” she tells them. “Have fun.”

It’s important to Julia that her students understand that they’re learning not only science concepts, but a way of thinking. She says, “A big part of InquirySpace is getting students to see the why.”

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant DRL-1621301. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.