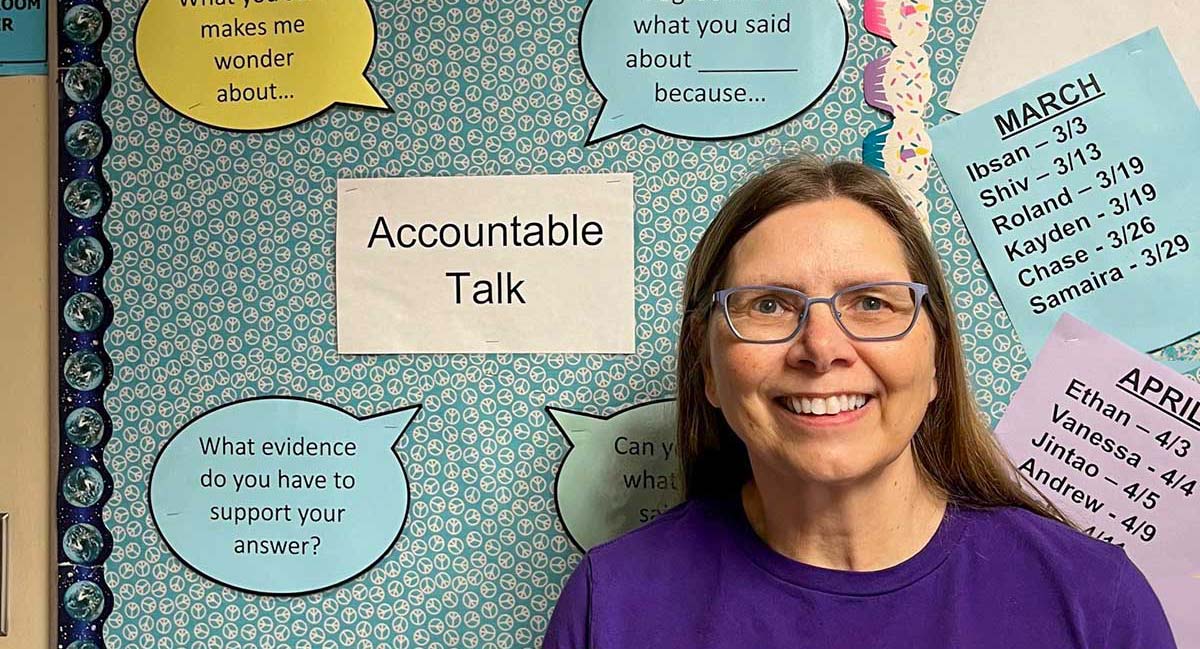

Teacher Innovator Interview: Marian Murembya

Marian Murembya was the fifth child in her family. She laughs when she describes her parents as “worn out” by the time she came along, but she’s glad for what that offered her childhood. “I was a free range kid who did a lot of exploring,” she muses. Her parents also encouraged Marian and her siblings to ask questions, which she did in abundance. These qualities would become the touchstone of her educational philosophy.

But her path to the head of the classroom was not straight-forward.While Marian took education courses during college—she figured they would be helpful for future parenting—she did not become a teacher immediately after graduation. Instead, she took a job as a deckhand on Lake Superior, then wrote for a local magazine, and worked in the printing business.After a decade of “doing all kinds of different things,” she moved from the Upper Peninsula to Okemos, Michigan, and opened a children’s bookstore, where “it was nice to see kids get excited about learning.” Two years later, after the bookstore closed, she earned a teaching certificate, so she could help more children experience that same excitement.

During a pilot program at Michigan State University (MSU) for pre-service teachers, Marian was introduced to a series of math methods courses, which spoke to the way she had learned. The middle grades math project, a precursor to MSU’s Connected Mathematics Project (CMP), emphasized questioning and collaborative problem solving.

Marian has been a middle school mathematics teacher in the Okemos district for over 30 years, teaching the CMP curriculum through all its versions. She is now a research participant in the Digital Inscriptions project, a collaboration between the Concord Consortium and Michigan State University, which has embedded CMP into our Collaborative Learning User Environment (CLUE) platform.

Despite the new online platform, Marian has stuck to some of her tried-and-true methods. She still groups her students in the same way whether they’re working online or with paper and pencil, and she sets the same expectations for how they should talk to each other when solving math problems. Another constant is her consistent use of two questions she asks her students: Why do you think that? and What do others think?

According to Marian, the biggest change is how students are learning within CLUE. “They’re more willing to try things because the digital tools allow them to do that.” Marian goes on to say, “Technology is a good thing, but kids need to know what to do with it.” For instance, while she doesn’t require that her students plot points by hand (the technology can assist with that task), she is clear that they need to be able to see the patterns and relationships in the graphs they make. Students, she says, should “muck about in the math.”

Marian is also excited by CLUE’s ability to allow students to join their classmates in online groups from anywhere and for her to see their work in progress. During COVID, for example, students from home could join groups, and she recently had a student who was in India participate in group work from a distance.

Marian thinks deeply about how her students are thinking and “what things are going to trip them up.” Her fondness for questions and problem solving led her to organize a Tuesday night “math circle” where students solve math problems for fun. Her approach is much like one of her favorite fictional characters, the inquisitive private investigator in the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series. To Marian, math is just another delightful mystery to unravel.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. DRL-2200763. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.