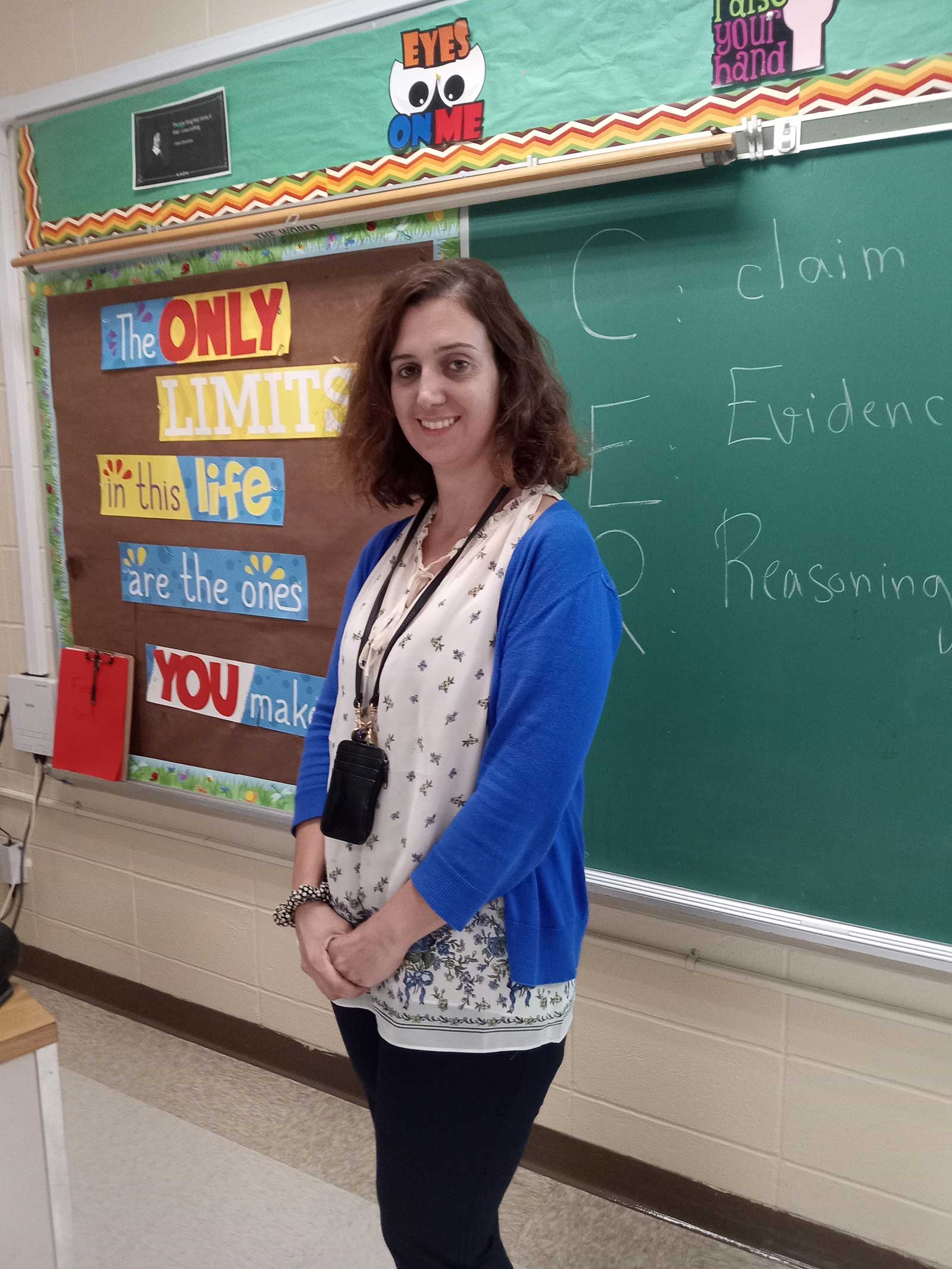

Teacher Innovator Interview: Jessica Sudah

Middle school science teacher, New Brunswick, New Jersey

Jessica Sudah is a self-described introvert, but she says, “I found my voice in the classroom. I found myself in the classroom.” When Jessica discovered that the goal of the Bio4Community curriculum was to honor student voices and experiences, she wanted to learn more. At the first curriculum design meeting, she witnessed seventh grade students talking to project researchers from Rutgers University, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and the Concord Consortium. She was hooked. “I loved that interaction. They always tell you to use student voice to change your curriculum. This was an actual, tangible way to see it backed by research.”

Before becoming a teacher, Jessica studied microbiology and conducted research in neurology, so the Bio4Community curriculum on the biological and physiological mechanisms of stress appealed to her. The unit, co-designed by researchers, teachers, and students, aims to engage middle school students in an inquiry-based biology learning environment where they develop their ideas and decide what is relevant and what counts as “valid” knowledge. As part of the curriculum design team, Jessica describes learning to see different points of view and the importance of getting to common ground. The key, she says, is putting students first.

When she implemented the curriculum in her classroom last spring, she was thrilled with the connections she made with her students. Because she teaches grades six through eight, she felt that she already knew the seventh graders—“their personalities, their fears, their ideas”—but she credits the Bio4Community curriculum for deepening that relationship. “The first thing the curriculum did was to build connections,” Jessica notes. From the outset, a storyboard allowed both Jessica and her students to share their life stories. According to Jessica, the relationships that resulted from that experience helped her learn about stress in her students’ lives, both at school and at home—from deadlines for school assignments to the responsibility of caring for siblings. This led her to rethink her approach to homework.

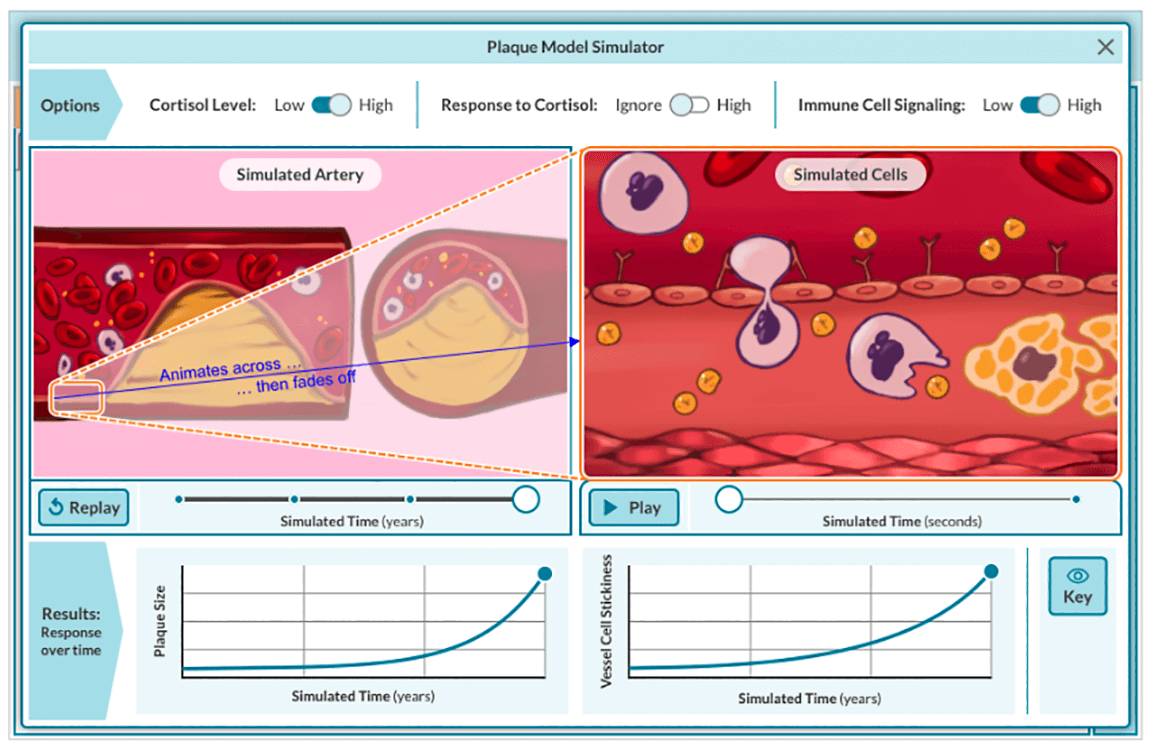

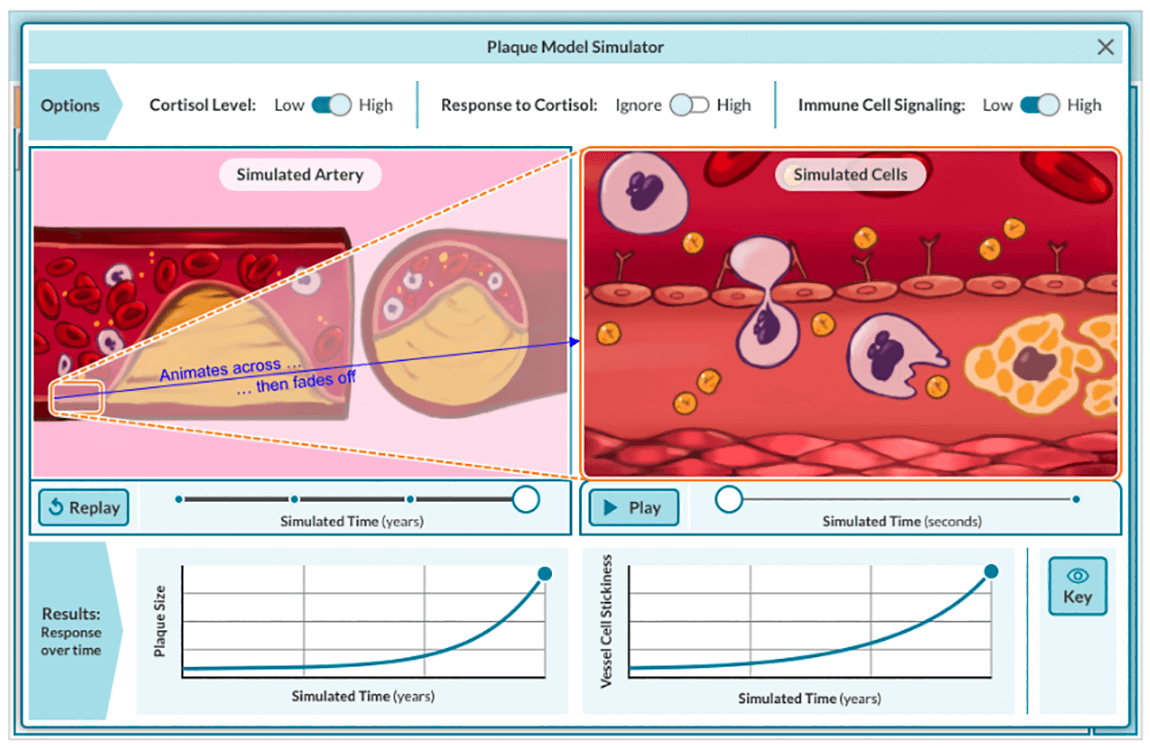

As part of the curriculum, students drew models of the body under both short-term and chronic stress. Although Jessica led the class through the first model-building experience, her students took charge of the second session. They developed a consensus model of chronic stress, integrating all the body systems based on case studies they had examined in groups. “The kids were very involved and engaged in the science,” she reflects. “They were excited and proud of their work.” As was Jessica. When the principal visited the classroom and asked about the role of the brain in stress, one student described how the prefrontal cortex is responsible for focus and regulation and how stress affects neurological connections. Jessica recalls how the rest of her students “were surprised by their own classmate saying all these big words. It was a big deal. They all clapped!”

Jessica believes Bio4Community was successful because the curriculum was culturally responsive; she says the design team “knew the community, the stressful events, and some of the culture.” But she admits that it’s also a difficult curriculum because it brings up issues of social justice. For example, Bio4Community considers causes of stress, such as racial discrimination. “That’s the more sensitive part of the curriculum,” Jessica explains. “I wasn’t sure how to deal with it myself at first and I realized the kids had the same feeling as me.” But seeing both a community elder and another teacher modeling how to talk about such stresses in their lives helped open the door for students to express themselves.

For Jessica, it’s all about incorporating students’ voices into the curriculum. She wants her students to find their voices in the classroom, just as she has.

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under grant DRL-200515. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.